The Woods Road Estates: A Primer

Aside from the gifts so generously bestowed by nature, one cannot underestimate the impact of the forty-odd estates built along the Hudson River by members the Livingston Family in defining our region’s special character. Nowhere is this better exemplified perhaps, than the remarkably intact string to the north of Clermont State Historic Site on Woods road. Shining examples of preservation, conscientious stewardship, and pride of place, they are also an enduring physical reflection of the intricate web of Livingston inter-familial relationships.

Original Entrance to Clermont

Marked by charming gatehouses and tantalizing long tree-lined drives, the homes (along with their outbuildings and/or farm complexes) are hidden from public view. In all but one instance they remain in private hands. While each of them has witnessed enough ups and downs and colorful stories to merit their own post, for the sake of relative brevity I limit this one to an overview and collective history of them all.

Background

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, most of the land on which the Woods Road estates now stand was part of the larger Clermont estate. Two mansions graced the property; Clermont, which served as a dower house for Margaret Beekman Livingston,

Clermont

and a newer mansion a few hundred yards to the south built for her son Robert (more popularly known as the Chancellor).

the Chancellor's Mansion

The Chancellor had two daughters, and the estate was eventually divided between them. The northern portion, consisting of the Clermont mansion and roughly two thousand acres, went to his elder daughter Elizabeth (Betsey) and her husband (as well as third cousin) Edward P Livingston.

Betsey Livingston Livingston

Betsey bore ten children over twenty years, though when she died in 1829 at the age of forty-nine only five survived her (not an uncommon occurrence in an era of high child mortality rates, no matter what one’s socioeconomic status). Despite her widowed husband’s remarriage in 1832 to Mary Broome, a woman just a few years older than his eldest daughter Margaret, the remaining children expected the family estate to be theirs when he died. Much to their consternation, when Edward passed way in 1843 he bestowed not only the handsome, if not quite princely sum of $20,000, but also Clermont itself upon the pretty head of his second wife.

Believing she had conspired to rob them of their rightful inheritance, the outraged siblings united against their stepmother, filing a lawsuit claiming among other things that she had tampered with the will. When the suit was thrown out of court, they planned another. The second Mrs. Livingston, having no deep connection to Clermont nor a desire for a costly and protracted legal battle, eventually agreed to vacate the mansion, taking her $20,000 and a good deal of the home’s furnishings with her (for more you can read this post from the Clermont blog). According the Clare Brandt’s The Livingstons, An American Aristocracy, once they had vanquished their mutual foe, the siblings began squabbling amongst themselves over their fair share of Clermont. The two brothers brought suit against their three sisters in chancery court over the validity of a map (it is not clear who drew it up) dividing Clermont’s land and tenant farms equally between them. Although it might seem greedy on the surface, one should consider the times in which they lived.

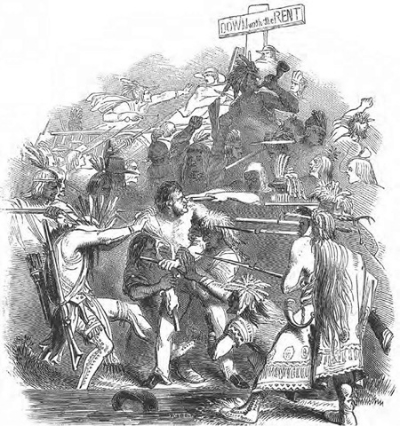

The economic lifeblood and social prestige of the Livingston family was rooted in the colonial Manor system. The family’s vast landholdings were farmed by tenant farmers, bound by “perpetual”, often multi-generational leases which stipulated the yearly rent and labor owed to the “Lord of the Manor”. When the family was at its zenith (owning over 750,000 acres), their holdings were so vast that the collection of past-due rents and enforcement of rules governing timber and mineral rights were often lax. Over the next several generations, as the family grew exponentially, the land was divided into smaller and smaller tracts, and its members now began to count their holdings in the mere thousands, as opposed to tens of thousands of acres. Subsequently the income from each individual tenant farm took on a greater significance. They began to take steps to collect past due rents dating back years or in some cases evict tenants. This was a leading cause of the “Anti-Rent” movement”. The tenants rebelled against the great landowning families, often with violent, or in some cases deadly repercussions for the hapless rent collector.

Tenants disguised as Indians attacking a sheriff

They also took legal action, challenging the leases in court, claiming that the legality of the Livingston’s original acquisition of their land was murky at best, fraudulent at worst. In 1844, the family scored a victory in court, leading them to believe the tenant-landlord system was secure for the foreseeable future. For the five children of Betsey Livingston, who would now be counting their property in the hundreds, as opposed to thousands of acres, each tenant farm not only represented income, but also a unit family pride.

Layered over this was perhaps a more significant societal factor. In that era, aside from whatever dowry the bride’s family might settle on a couple, a woman’s income, comfort, and financial security was the responsibility of her husband once she was married. Although their mother Betsey was considered a great heiress, there had been no sons for her father to pass his fortune on to (in fact as a testament to the times, the Chancellor left his shares in the Great Northern Steamboat Company to his two sons-in law as opposed to his daughters). While the youngest sister Mary was not married with a husband to provide for her, the status of an unmarried woman at that time was far from enviable. They were usually considered wards of the family, living with a married relative, seldom having their own households or property. Given this, one can understand why the two brothers would balk at their incomes being significantly diminished to give their sisters an extra income stream in addition their husband’s resources. As for Mary, what need would she have for rental income from tenant farms when living under one of their roofs?

Remarkably, the Livingston siblings were able to work out a division of their parent’s property that seems radically fair for the times. Each received a large tract of land large enough to support a working farm with half a mile of river frontage, along with a “suitable” number of the farms, (the two brothers garnering an appropriately larger share than their sisters). One only has to look a short distance south to see how easily it could have gone another way, for around same time the Betsey’s sister Margaret Maria’ children were dividing up their parents’ estate which included the Chancellor’s mansion and the southern half of Clermont. In that case, two brothers split the land between them while two sisters got none of it. Their respective inheritances settled, any disruptions to familial harmony seem to have been soon restored, physically evidenced by the internal system of private carriage roads connecting the estates they soon established on each of their river properties.

The Vertical lines represent public roads while the intersecting on the left are Livingston Carriage roads

Clermont

Clermont Livingston

The eldest brother (appropriately named Clermont) received the Clermont mansion and southernmost portion of the estate.

Clermont under Clermont Livingstons ownership

Unlike his brother and sisters who were settling in the newly fashionable precincts off of Fifth Avenue above 14th Street and used their estates more as country retreats, Clermont made, “Clermont” his primary year-round residence. After bearing two children, his wife, a distant cousin died. Perhaps mindful of the ruckus caused by his father’s second wife, the young widower made a much more pragmatic choice in his, Mary Swarthout Livingston, his former next door neighbor in the Chancellor’s mansion and widow of his cousin Montgomery.

The Second Mrs. Clermont Livingston

Unimpeachable socially, her photograph indicates she was also age appropriate with a head perhaps not quite as pretty as his former stepmother's!

Chiddingstone/Ridgley

Eldest sister Margaret Livingston and husband David Augustus Clarkson built a wooden frame home on her property immediately to the north of Clermont, which they dubbed Chiddingstone. Widowed in 1850, Margaret divided the estate between her two children after their marriages (she died herself in 1874). Her son Thomas Streatfield Clarkson, founder of a successful real estate firm in New York received the northern portion of the property on which his parent’s house stood. He soon razed it and around 1860 constructed an elegant, distinguished looking brick home in its place.

Chidingstone

The house, which successfully combines Italianate and classical elements, has recently been impeccably restored.

Photo: Rural Inelligence

Margaret’s daughter Elizabeth (married to George Gibbes Barnwell) received the southern half of Chiddingstone. Shortly after she passed away in 1860 the property was sold to William H Hunt of New Orleans, who bought it for his wife Elizabeth Ridgely (a great-granddaughter of Chancellor Livingston through his daughter Margaret Maria). Scarcely had they settled in, naming the property Ridgely when she died in 1864. Ridgley was then sold to John T Hall, who owned it for thirty years. After his death in 1895 William and Elizabeth Hunt’s son Thomas bought the place, bringing it back into the family fold. He most likely built the current mansion with its stuccoed formality and neo-regency massing.

The Hunts owned an apartment at 655 Park Avenue but considered Ridgley their home. After Thomas Hunt’s wife died in the 1940s, the Carmelite Sisters acquired the estate. Despite the encroachment of newer institutional buildings, the house and property still retain much of their grandeur.

Southwood /Midwood

Youngest sister Mary received the parcel next to her sister Margaret’s, naming it Southwood. In 1849 she married Levinus Clarkson, a first cousin of Margaret’s husband David (if there was a family that could give the Livingstons a run for their money in having a tangled thicket of a family tree, it may have been the Clarksons). The couple settled into a brownstone at 14 West 19th Street and soon built a comfortable house on her property in a transitional late Greek revival style with Italianate elements, adding a third story mansard roof later.

After Levinus died in 1860 Mary spent much of her long widowhood there, along with her sons Edward and Robert. When Robert married Miss Mary Otis in 1886, his mother gave them the northern portion of the property, on which they built a comfortable second empire frame home, naming it Midwood.

Edward remained unmarried, continuing to share Southwood with his mother until her death in 1898. In 1913, he sent tremors of shock rippling through the Woods Road cousinage by marrying Rachel Coon, a woman not only forty years younger but also from a local middle class family. of all things! Both estates were sold out of the family in the twentieth century and are well cared for today by their respective owners. You can see more of pictures of them today by clicking here for Southwood, and here for Midwood.

Pine Lawn (later Holcroft)/Oak Terrace

Elizabeth Livingston Ludlow

Middle daughter Elizabeth and husband Dr. Edward Hunter Ludlow built a charming cottage named Pine Lawn on her property adjacent to Southwood, intending to retire from the bustle of New York and lead a quiet country life there. Country retirement evidently didn’t suit Dr. Ludlow very well, for by 1850 he founded a new real estate firm in New York City, later becoming a trustee of the medical department of Columbia Medical College and President of the New York Real Estate Exchange, while amassing a significant fortune along the way. Although the Elizabeth didn’t marry a Clarkson like her sisters, the Ludlows made their own contribution towards tangling the family tree. Two years after their daughter Mary married Valentine Gill Hall, Jr., their son Edward Livingston Ludlow married Valentine’s sister Margaret. The Ludlows cottage was destroyed in the 1870’s, when a cinder from a passing train set the cottage ablaze. Around that same time or shortly after, Elizabeth divided her property between her two children. Son Edward built a handsome red brick residence (with a slate roof, perhaps to ward off train-borne sparks?) on the site of his parent’s cottage,.

Pine Lawn/Holcroft

Edward Ludlow sold the “new” Pine Lawn to Howard and Alice Delafield Clarkson (Howard also a great-grandson of the Chancellor’s through his daughter Margaret Maria) who renamed it “Holcroft” in deference to the Clarkson family seat in Potsdam New York. It is still owned by their descendants today. Daughter Mary and Valentine Hall erected a large, buff brick second empire mansion named Oak Lawn (later Oak Terrace) on their portion.

Oak terrace Vintage View

Their daughter Anna married Elliot Roosevelt, and today Oak Terrace is today known as the place where a young Eleanor Roosevelt spent a good deal of time after mother’s death. Although the house had been allowed to deteriorate almost beyond the point of repair over the past sixty years, new owners have rescued the building, embarking on a complete restoration.

Oak terrace at the Beginning of the Restoration Process

Northwood

The youngest son Robert Edward received the most northerly portion of Clermont, appropriately if not imaginatively naming it “Northwood”. He significantly enlarged its footprint by purchasing adjacent farms to the north and east, and eventually established a commercial orchard there. He married Susan de Peyster Clarkson in 1856 (a first cousin once removed to both his sister Mary and Margaret’s husbands!). The only one of the siblings to boast a Fifth Avenue address (271)

271 Fifth is the brownstone to left of the Calumet Club on the corner of 29th st.

it is perhaps fitting that the home Robert built at Northwood was the most “high style” of the brothers and sisters.

The Second empire mansion’s soaring ceilings, wide halls and elegant, restrained exterior speak to good taste and refinement. It remained in the family until the second half of the twentieth century, and is very well maintained to this day.

It is interesting to note, with three of the five siblings marrying Clarksons, four maiden Clarkson sisters purchasing the Chancellors mansion in 1858, and the marriage of Howard Clarkson’s (of Holcroft) daughter Alice Delafield Clarkson to Clermont Livingston’s son John Henry Livingston a generation later, it might appear that, the Clarkson family could rightfully claim dominance over the Livingstons on the Woods Road estates, as the family had resided in all but one of them (Oak Terrace)by the early twentieth century. In reality, by this point there had been so much intermarriage between the two clans that a Clarkson would also be considered a Livingston, and vice versa! In any case I say thank you to Clarksons, Livingstons, Livingston-Clarksons and CLarkson-Livingstons, for their architectural legacy and unique enclave they created,making Woods Road a very special corner of the Hudson Valley!