The Tales They Tell, Part 1: Clermont, From Colonial to Queen Anne and Back to Colonial Again

I am fortunate to live in a region offering a trove of historic homes open to the public. Whether simple colonial farmhouses or beaux-arts fantasies, a quick exterior observation can lead one to mistakenly assume many appear today as they always have; unaltered architectural expressions of one person’s vision or the era in which they were originally constructed. Most however, belie far more complex and interesting stories. Many have changed in appearance over time, some quite drastically. Whether to accommodate expanding families, adapt to modern lifestyles, suit personal taste or ambition, keep up with the Joneses or a combination of the above. In some, the original structure and style is clearly visible, while in others it requires a harder look and some imagination to recognize it under later additions and ornamentation. Also interesting to learn are the unrealized plans for some of them that were never executed due to lack of funds, indecision, or simply a change in ownership.

Part I

Clermont: From Colonial to Queen Anne and Back Again

Clermont, home to seven generations of the Livingston Family, is the first example I will look at, as well as the oldest. When originally constructed around 1740, the large home perched on a bluff above the Hudson River was heralded as one of the most imposing and beautiful country seats between Albany and New York City.

Its first major physical transformation occurred in 1777, when it burned nearly to the ground after British troops set fire to it during the Revolutionary War. As soon as it was safe to return, Margaret Beekman Livingston, the indomitable matriarch of the family and daughter in-law of the original builder, oversaw a complete reconstruction of the mansion.

Margaret Beekman Livingston

Despite entreaties by her family to wait until the war was over, the reconstructed house was habitable by 1781. Whether architectural innovation was at a low ebb during wartime, the attachment to the home where she and her husband raised their ten children was overwhelmingly strong, or perhaps even the formidable Margaret wanted to thumb her nose at the enemy, demonstrating just how resilient she and the nascent country were. For whatever reason, the new mansion which rose upon the foundations and charred walls of the old was by all accounts strikingly similar, if not an exact replica of the original.

A flurry of new country estates were established along the Hudson (including many built by Margaret’s children) In the decades following the war. By the time Margaret’s granddaughter Betsey and her husband (as well as third cousin) Edward P. Livingston inherited Clermont in the early nineteenth century, it was no longer one of the most imposing homes in the region.

Betsey Stevens Livingston Livingston

Edward P Livingston

By 1805 a one-story wing had been added to the north side of the mansion. In the 1840’s it was joined by a flanking one to the south.

Combined with shallow piazza was extended across the river façade of the house, and the first floor windows cut down the meet the porch floor, Clermont presented a more horizontal, symmetrical, if somewhat chaste presence to the world over the next several decades.

Edward and Betsy’s grandson John Henry Livingston (the last master of the house) decided to expand the house again in the 1870s.

John Henry Livingston

Many of his relatives and neighbors were also building or enlarging their homes during this period, oftentimes adding a second empire mansard roof atop them to gain an extra floor.

Oak Hill, John Henry’s childhood home, expanded in the 19th century with a mansard roof

John Henry opted for something a bit different however. Perhaps to remind people of Clermont’s role as the historic center of Livingston Manor, he added a striking, chateauesque style roof, generally associated with larger, more palatial buildings, atop the mansion. It dramatically increased Clermont’s height, creating a much more imposing silhouette.

Clermont with its chateauesque roof

By 1893, the south wing gained an additional two stories, raising it to the same height as the center of the house. With variations in dormer treatments, contrasting shutters, and a much larger veranda with a semi-circular porch dominating its river façade, Clermont took on some of the outward characteristics of the Queen Anne style then in vogue.

Things took a decidedly different turn after John Henry’s third marriage to his distant cousin Alice Delafield Clarkson.

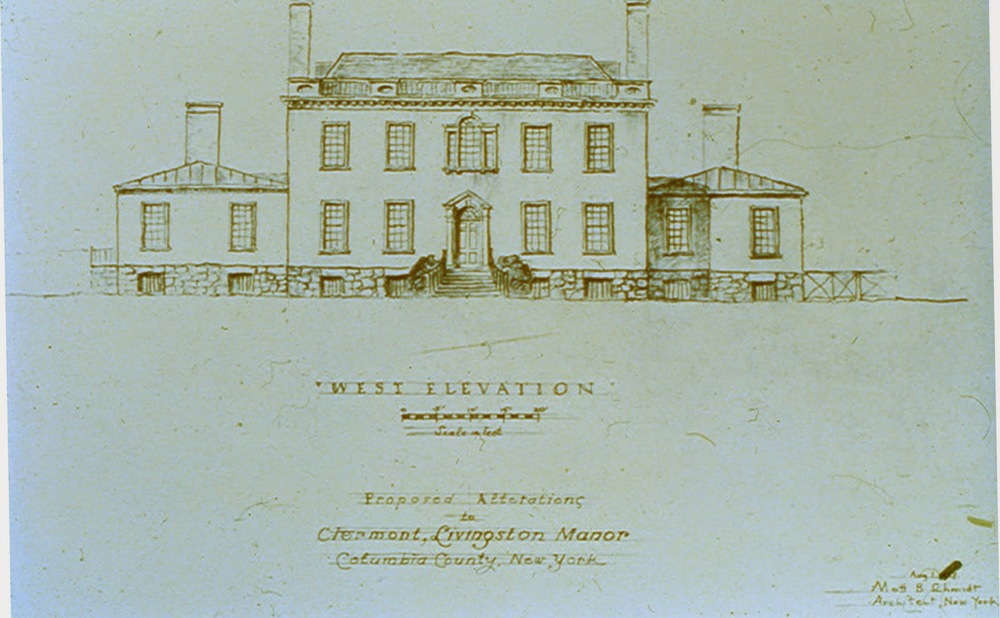

If there was anyone more proud of the family’s glorious past than John Henry, it was Alice. The couple planned the last major modernization of the house, creating a monument to the family’s social and financial heyday, while getting rid of the now out fashion victorian additions at the same time. In the Clermont archives a drawing by society architect Mott Schmidt for the Livingston’s, proposing the removal of the steeply pitched roof and upper floors of the south wing.

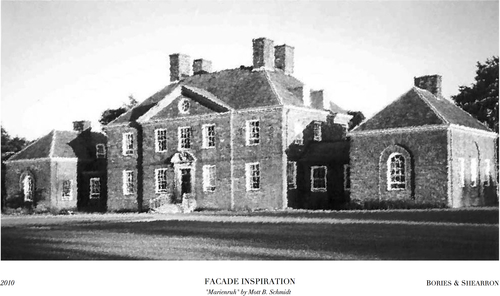

Had it been executed, Clermont would have resembled it’s 1840’s appearance once again, as well as an interesting similarity to Marienruh, the estate Mott Schmidt was designing nearby in Rhinebeck for distant cousin Alice Astor and her husband Serge Obolensky.

Whether the idea proved too costly, or too ambitious given John Henry’s age (he died in 1927), the plans were never followed. Instead, a compromise of sorts was reached. The chateauesque roof and upper floors of the south wing remained, but the wide veranda and porch disappeared, the contrasting shutters were removed or painted white, and a restrained, colonial revivalized house emerged, very similar to what we see today.

Above: Clermont in the 1930s , Below: Clermont Today

For more information about Clermont, please visit the Friends of Clermont website.

Part 2 in this series will look at Montgomery Place's Exterior Story