The mid-decades of the nineteenth century saw a marked change in the character of the grand homes being built in the Hudson Valley. As the vast agricultural estates of the Livingston Family were broken up amongst dozens of descendants, associates and relations, replaced by elegant country retreats, solid Georgian and federal style structures gave way to Greek temples, gothic cottages, Norman castles and Tuscan villas, reflecting the full flower of Romantic Movement.

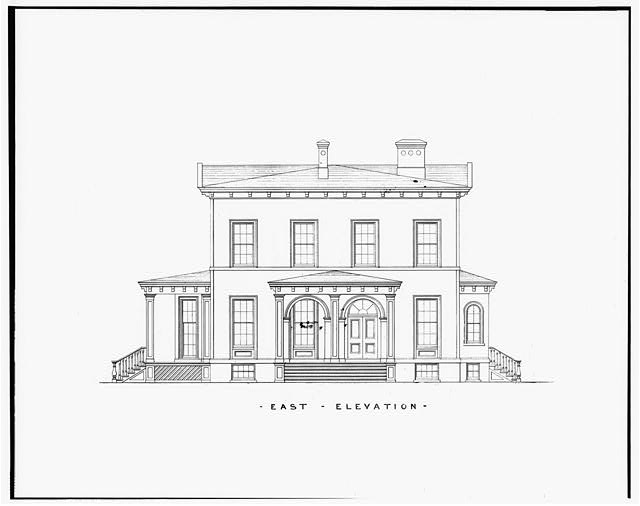

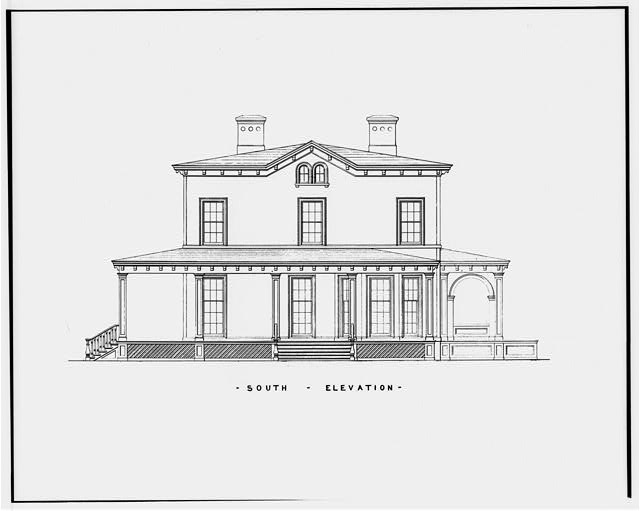

In 1852 Thomas Holy Suckley, wealthy New Yorker and Livingston descendant, purchased a 32-acre meadow from his distant cousin and fellow devout Methodist Mary Freeborn Garretson’s Wildercliff estate. The property, located a few miles south of Rhinecliff commanded unparalleled views down the river (the same claim was made by nearly every other estate owner who possessed Hudson River views, so it is open to debate). Suckley promptly hired fashionable New York City architect John Warren Ritch to design a country retreat for it in the Italianate style.

Though the style easily incorporating picturesque elements, including belvedere type towers, elaborate window crowns, heavy bracketing and corbels enhancing wide eaves and porches, Suckley would have none of that. Ritch produced one of the simplest, plainest versions of an Italian villa possible for his sober, pious client.

While definitely not one of the showiest places on the Hudson, it was a comfortable home, providing a capacious retreat from the bustle of New York City for Thomas’s family, which included his wife, his two unmarried siblings, and soon, three children. Thomas was not totally immune to the prevailing romanticism of the times however. Within two years, his estates rather conventional name “The Cedars” was jettisoned in favor of the German-inspired “Wilderstein”.

While definitely not one of the showiest places on the Hudson, it was a comfortable home, providing a capacious retreat from the bustle of New York City for Thomas’s family, which included his wife, his two unmarried siblings, and soon, three children. Thomas was not totally immune to the prevailing romanticism of the times however. Within two years, his estates rather conventional name “The Cedars” was jettisoned in favor of the German-inspired “Wilderstein”.

The family enjoyed their life at Wilderstein for several decades, until the 1870s, which saw Thomas’s wife, siblings, and only daughter all die within a few years of each other. If there was a silver lining to this somber cloud, it was that the entire family fortune would be consolidated on the head of his surviving son Robert, who married Elizabeth Montgomery (nicknamed Bessie) in 1884. Robert Bowne Suckley

Robert Bowne Suckley Elizabeth Montgomery As both of Thomas’s siblings died childless, the size of Robert’s eventual inheritance increased five to six-fold over what he might have otherwise expected.

Elizabeth Montgomery As both of Thomas’s siblings died childless, the size of Robert’s eventual inheritance increased five to six-fold over what he might have otherwise expected.

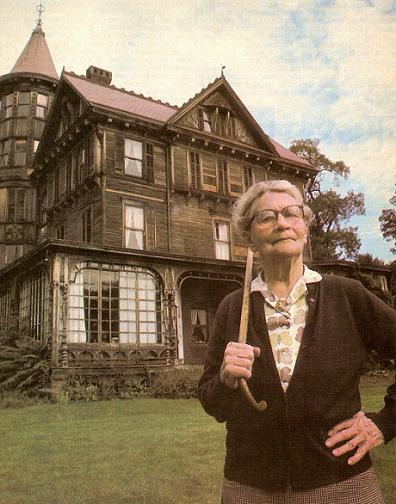

When Thomas passed away in 1888, Robert and Bessie wasted no time in spending their substantially increased income. Unfettered by the dour principles of strict Methodism, Robert hired Poughkeepsie architect Arnout Canon to transform the simple home they inherited into something more reflective of the times and the couple’s character. Transform it he did. A large servants and kitchen wing sprouted off the north side of the house, while the original structure ballooned upwards, gaining a full third floor topped by large attic story under a steeply pitched roof, replete with multiple gables and dormers. Wide verandas, an elaborate porte cochere, and porches wrapped around the mansion, helping to ameliorate its dramatic increase in height The piece de resistance of the new Wilderstein though, was a soaring five story tower with a candle snuffer top facing the river. The elaborate exterior woodwork and trim featuring a multiplicity of surface treatments including faux half timbering and shingles was accentuated by a vigorous, polychromatic color scheme. Joseph Burr Tiffany (distant cousin of Louis Comfort) was hired to design the interiors. The large number of stained glass windows seen on the exterior of the house bears witness to jewel-like interiors he created in a number of different historical styles.

The elaborate exterior woodwork and trim featuring a multiplicity of surface treatments including faux half timbering and shingles was accentuated by a vigorous, polychromatic color scheme. Joseph Burr Tiffany (distant cousin of Louis Comfort) was hired to design the interiors. The large number of stained glass windows seen on the exterior of the house bears witness to jewel-like interiors he created in a number of different historical styles.

The proud Queen Anne Butterfly that emerged from Thomas’s’ Italianate chrysalis housed Bessie and Robert, their six children, numerous servants and relations. The property on which it sat expanded to the same degree through the acquisition of neighboring parcels. On it sprouted a gate lodge, Carriage house, greenhouse, potting shed and boathouse. Even after all this, more additions were envisioned to the home itself. A cast iron conservatory was purchased, most likely to be added off the dining room. Robert had plans drawn up for a, half timbered billiard room addition on the second floor that would sit atop the porte cochere.

The property on which it sat expanded to the same degree through the acquisition of neighboring parcels. On it sprouted a gate lodge, Carriage house, greenhouse, potting shed and boathouse. Even after all this, more additions were envisioned to the home itself. A cast iron conservatory was purchased, most likely to be added off the dining room. Robert had plans drawn up for a, half timbered billiard room addition on the second floor that would sit atop the porte cochere.

None of these latter plans came to fruition however. The financial panic of 1893 had a severe impact on the family’ investments, and their fortunes never fully recovered. By 1897 the family followed the example of many others in their class and similar situation. They shuttered Wilderstein and decamped for Europe in order to economize, where one could maintain a proper lifestyle at a substantially lower cost. The Suckley’s remained abroad for the better part of a decade. It was not until 1907 that they resumed fulltime residence at Wilderstein again. During that time, a see change in taste had occurred. Eccentric Queen Anne and Victorian excess were no longer in fashion, supplanted by more academic and restrained European and colonial revival styles. Not much could be done to radically reconstruct the house again. The Suckley’s instead turned to paint. The polychrome exterior was replaced first by a cream coat with brown trim, then an all-brown palette, in 1910. If they couldn’t keep up with the Jones, then at least they would at least try to be a little less conspicuous. Early 20th Century Painting of House showing brown color scheme

Early 20th Century Painting of House showing brown color scheme

Robert’s death in 1920 had the opposite effect on the family finances than his father or grandfather’s. The greatly diminished Suckley trusts were now effectively split six ways, between Bessie and their five surviving adult children. As the family’s fortunes faded, the Suckleys often quietly received furniture and belongings no longer being used by their wealthier relations. Wilderstein became a repository for the an irreplaceable mix of trash and treasure; it’s five floors overflowing with an eclectic mix of furniture, antiques, furs, artwork and assorted quelque chose intimately associated with the great families of the Hudson Valley. Wilderstein's White and Gold Salon, 1930'sThere were no more changes made to the outward appearance of the house (not even another coat of paint after the 1910 one) since the family couldn’t afford to do much more than hold the place together. As the twentieth Century trudged on, the five surviving children of Bessie and Robert passed away, one by one until only the eldest daughter Daisy remained living at Wilderstein.

Wilderstein's White and Gold Salon, 1930'sThere were no more changes made to the outward appearance of the house (not even another coat of paint after the 1910 one) since the family couldn’t afford to do much more than hold the place together. As the twentieth Century trudged on, the five surviving children of Bessie and Robert passed away, one by one until only the eldest daughter Daisy remained living at Wilderstein. Daisy in her 90's After her passing in 1992, the home was taken over by the Wilderstein Preservation, a private nonprofit organization she helped form to protect the family home for the public. Since taking over the property, the organizations energy, enthusiasm and successful fundraising have not only saved Wilderstein, but also restored it to a state of almost unremembered former glory. Ironically, the organization got a nice financial boost from the Suckley family trust. Dispersed amongst Robert’s five children upon his death, it was reconsolidated little by little when each of they in turn passed away, growing again under prudent management. As only one of the siblings married and had children, both of whom died childless themselves, Wilderstein Preservation became the sole beneficiary of the tidy little fortune.

Daisy in her 90's After her passing in 1992, the home was taken over by the Wilderstein Preservation, a private nonprofit organization she helped form to protect the family home for the public. Since taking over the property, the organizations energy, enthusiasm and successful fundraising have not only saved Wilderstein, but also restored it to a state of almost unremembered former glory. Ironically, the organization got a nice financial boost from the Suckley family trust. Dispersed amongst Robert’s five children upon his death, it was reconsolidated little by little when each of they in turn passed away, growing again under prudent management. As only one of the siblings married and had children, both of whom died childless themselves, Wilderstein Preservation became the sole beneficiary of the tidy little fortune.

The funds helped meticulously restore the exterior, returning it to its Queen Anne polychromatic color scheme, which might have seemed strange to the latter generations who lived there, but sets off the architecture superbly. Still, if one looks closely, mentally stripping away the upper floors, tower and porte cochere, the simple Italianate core of the comfortable, sober house built for Thomas Suckley is surprisingly easy to discern.

Still, if one looks closely, mentally stripping away the upper floors, tower and porte cochere, the simple Italianate core of the comfortable, sober house built for Thomas Suckley is surprisingly easy to discern. This is the third installment in my Fourt Part Series. To read the first installment on Clermont, click here, and the second on Montgomery place, click here. For more information on Wilderstein and the Suckley family, please visit the Wilderstein Preservation's Website

This is the third installment in my Fourt Part Series. To read the first installment on Clermont, click here, and the second on Montgomery place, click here. For more information on Wilderstein and the Suckley family, please visit the Wilderstein Preservation's Website