This is the second of a four part series looking at the evolution in appearance of some Hudson Valley homes, and some of the personalities that shaped them. To see the first intallment, click here.

In 1805, a new mansion arose in the midst of a commercial farm and nursery roughly ten miles to the south of Clermont, built for Janet Livingston Montgomery. Family and associates were a bit surprised when the middle-aged, childless widow (of Revolutionary War General Robert Montgomery) already in possession a comfortable estate outside the village of Rhinebeck took on this new venture. A drawing of Mrs. Montgomery reveals the same formidable features of her mother, Margaret Beekman Livingston however, whose drive and determination she most likely also inherited.

sketch of Janet Livingston Montgomery

sketch of Janet Livingston Montgomery

Prior to the home’s construction, she implored her brother Robert, then serving as Minister to France, to send her house plans in the latest French style, reflecting the family’s (and young nation’s) decided lean towards all things French as opposed to British during that era. Robert apparently didn’t come through with anything though. Her mansion overlooking the Hudson, dubbed Chateau de Montgomery, featured modish French-influenced interiors and furnishings, still bore a vague, though restrained almost to the point of severity, french exterior to the world. Early sketch of Chateau de MontgomeryJanet died in 1828, leaving the property to her youngest brother Edward and his wife Louise D'Avezac Moreau. Haitian-born of French descent, the new chatelaine of Chateau de Montgomery was exotic, elegant and decorative looking as Janet was practical.

Early sketch of Chateau de MontgomeryJanet died in 1828, leaving the property to her youngest brother Edward and his wife Louise D'Avezac Moreau. Haitian-born of French descent, the new chatelaine of Chateau de Montgomery was exotic, elegant and decorative looking as Janet was practical. Louise Livingston The couple immediately began putting their stamp on the property, pushing utilitarian farming elements well away from the house, transforming the estate into an ornamental country place, with the advice involvement of AJ Davis and AJ Downing. Whether out of respect for Janet or simply due to the intense activity outdoors, the house (renamed Montgomery Place), remained relatively unchanged during Edward’s lifetime. After his death in 1838 however, all bets were off. The widowed Louise Livingston, aided and abetted by her daughter Coralie Barton and architect AJ Davis, began to drastically alter the look of the mansion. Pavilions were added to the north and south.

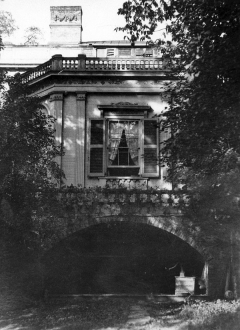

Louise Livingston The couple immediately began putting their stamp on the property, pushing utilitarian farming elements well away from the house, transforming the estate into an ornamental country place, with the advice involvement of AJ Davis and AJ Downing. Whether out of respect for Janet or simply due to the intense activity outdoors, the house (renamed Montgomery Place), remained relatively unchanged during Edward’s lifetime. After his death in 1838 however, all bets were off. The widowed Louise Livingston, aided and abetted by her daughter Coralie Barton and architect AJ Davis, began to drastically alter the look of the mansion. Pavilions were added to the north and south.  South Pavilion

South Pavilion north wingOne contained a closed addition, the other a sublime pavilion; both featuring arches and Corinthian pilasters. A porch was also added across the river façade at the same time. Although Davis was a proponent of the irregular and picturesque in architecture, his clients insisted the house retain a classic feel (perhaps out of deference to Edwards long role as a public servant).

north wingOne contained a closed addition, the other a sublime pavilion; both featuring arches and Corinthian pilasters. A porch was also added across the river façade at the same time. Although Davis was a proponent of the irregular and picturesque in architecture, his clients insisted the house retain a classic feel (perhaps out of deference to Edwards long role as a public servant). Edward Livingston To enliven the experience, he added a multitude of decorative elements; swags, urns, and medallions were applied to any and all possible surfaces, turning the house into a neo-classic confection of sorts. In the early 1860s Coralie Barton again turned to AJ Davis to make changes to the house.

Edward Livingston To enliven the experience, he added a multitude of decorative elements; swags, urns, and medallions were applied to any and all possible surfaces, turning the house into a neo-classic confection of sorts. In the early 1860s Coralie Barton again turned to AJ Davis to make changes to the house. Coralie BartonDavis duly prepared designs to embellish the front with a semi-circular portico inspired by the temple of Vesta in Tivoli (Italy, that is, not the village several miles to the north of Montgomery Place), along with a new third story featuring a raised roofline and balustrade.

Coralie BartonDavis duly prepared designs to embellish the front with a semi-circular portico inspired by the temple of Vesta in Tivoli (Italy, that is, not the village several miles to the north of Montgomery Place), along with a new third story featuring a raised roofline and balustrade.  Davis proposed alterations

Davis proposed alterations Temple of Vespa, near TivoliCoralie was enchanted by the new portico design, but found the cost and complications of adding a third story to the mansion too much. She planned on only having new porch constructed. As it was going up however, things went awry. However beautiful the new portico would be, it was obvious the overall appearance of the house would look squashed. Surviving letters to Davis from Barton imploring him for a solution reveal quite a bit about her personality, their client/architect relationship and the embellished prose of the romantic era.

Temple of Vespa, near TivoliCoralie was enchanted by the new portico design, but found the cost and complications of adding a third story to the mansion too much. She planned on only having new porch constructed. As it was going up however, things went awry. However beautiful the new portico would be, it was obvious the overall appearance of the house would look squashed. Surviving letters to Davis from Barton imploring him for a solution reveal quite a bit about her personality, their client/architect relationship and the embellished prose of the romantic era.

“The columns are up & the entablature is progressing. The whole thing per se is beautiful — but alas! It squashes down the whole home, & as one of the ancients said: Who has clapped my old house to the Temple of Vesta!' The addition to the top of the house becomes a necessity & is the only thing to save us from a monstrous incongruity ... ... Pray-pray-my dear Mr. Davis, think of what can be done ... You see, I am in despair ... ... You wicked man, with your Temple of Vesta to lead me to all this ruinous extravagance which I cannot now avoid without being ridiculous. "

Davis was in Barrytown a week later to work out an affordable, aesthetically pleasing solution. Instead of a raised roofline, the center balustrade was raised, further heightened by decorative urns to balance the overall composition. Mrs. Barton was thrilled, praising the results at length.

So successful was the final design that although the home continued for over a hundred more years as a private residence, no further substantial changes were made to the exterior. The house appears today much as Louise, Coralie and AJ Davis envisioned it, with Janet’s solid federal home still visible under it all,holding up the later decorative elements, wings, and balustrades quite handsomely.