The Belmont Boys and Girls Part 1: The King of Fifth Avenue and the Queen of Society

Thanks in part to the eponymous Racetrack and Stakes, Belmont is of the great gilded age names that continues to resonate in the modern ear. While their “heyday” may have been briefer than some other families, at a certain time newspapers would lump them as one of the “Big Three” along with the Astors and Vanderbilts, in New York and Newport society.

photo: bleacher report.com

The family’s rise coincided with that of the popular press and the public’s subsequent fascination with the lives of the very rich. The lives they led generated headlines, augmented by plenty of “fake news” pieces that burnished their reputations or heightened their notoriety. This multi-part post will take a look at the lives, homes and headlines of two generations.

Part 1

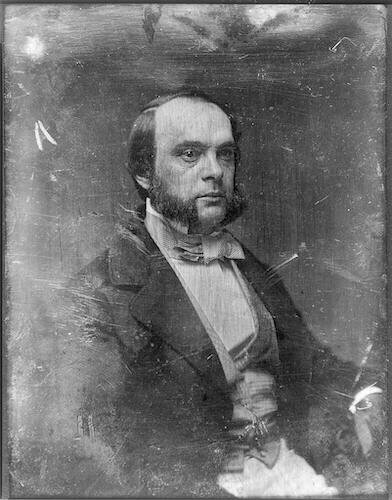

Early daguerreotype of August Belmont

August Belmont, who founded the family fortune, was born in Germany in 1813 to a Jewish family of modest means. Beginning his career as a teenage apprentice with the Rothschild bank in Frankfurt sweeping floors and running errands, he swiftly rose up through the ranks, sailing for Cuba to represent the firm’s interests there at the age of twenty-four.

19th century view of Rothschild Bank in Frankfurt

He stopped at New York City enroute. Reeling financially from the Panic of 1837, amongst the hundreds of firms that had collapsed in the chaos was the Rothschild’s American agent. Belmont stepped into the breach, founding the investment firm August Belmont & Company to represent the Rothschilds interests across the western hemisphere. It was an immediate success, and he became a very rich man.

His wealth established; Belmont’s attention turned towards politics. He was named Consul-General of the Austrian Empire at New York City in 1844 and later served as Chargé d’Affaires to the Netherlands after becoming a US Citizen. During the Civil he lobbied the leading financial firms in Europe to support the Union cause. In 1866 he was named National Chairman of the Democratic Party, a position he held until 1872.

With a personality to match his fortune, a permanent limp acquired from a duel in 1841, fondness for fast horses, gambling, and pretty sopranos, Belmont cut a colorful, if somewhat controversial figure in New York Society (it is said he inspired the character of Julius Beaufort in Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence). Fortunately, he married Caroline Slidell Perry, one of its leading belles in 1849.

Caroline Slidell Perry Belmont Image: Museum of the City of New York

Caroline was the daughter of naval officer Matthew C. Perry, who opened Japan’s ports to the West (and perhaps more importantly, helped spark the Victorian craze for ”japonisme”). Her uncle, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, was a great hero of the War of 1812 and she was connected to New York’s elite old mercantile clans through her mother’s family. While the virulent anti-Semitism that would later mark New York’s gilded age had not yet been fully codified, Belmont converted to Episcopalianism around the time of his marriage.

Anti-Semitic trope targeting Belmont from a 1872 illustration in Harper’s Weekly portraying him as Shylock.

The couple had a son named Perry in 1850 followed by August Jr, daughters Jane and Fredericka, then two more boys, named Oliver Hazard Perry, and Raymond. To house his growing family, Belmont purchased a large townhouse at 109 Fifth Avenue in 1857 for $90,000. He then paid the owner of the house next door a substantially higher amount ($130,000) in order to combine the two into a more palatially scaled mansion. He soon bought the lot behind them on 18th street to add on a conservatory and private art gallery, which also functioned as one of the few private ballrooms in the city at the time.

Photo: NYPL Digital Collections

As great wealth poured into New York during the 1850s, it launched an era of conspicuous consumption. For the most part however, it was confined to the “new money” elements. In contrast, restraint and understatement marked the lifestyles of even the wealthiest members of New York’s entrenched Knickerbocracy. The Belmonts changed all that. Running 109 Fifth Avenue along the lines of the great houses of Mayfair or Paris, they employed liveried footmen, hired a cordon bleu chef, and adopted formal dress for dinners. Belmont amassed a superb wine cellar and peerless art collection (occasionally opened to the public for charitable purposes). While the more conservative elements may have looked askance at the Belmonts’ extravagance and continental flourishes, the rest of the peers couldn’t resist the magnificent parties and superb dinners they hosted. As the Belmonts’ acquisitive lifestyle was mimicked by more and more in society, observers gave rise to the somewhat snide saying ‘Belmont keeps everything but the Ten Commandments “.

The dining room of the Belmont mansion photo: Museum of the City of New York Digital Collections

When the press covered a gala ball held at the Academy of Music to honor of the visiting Prince of Wales in 1860, they noted approvingly that a splendid diamond riviere, previously widely admired in the windows of Tiffany’s was now widely admired gracing the elegant neck of Caroline Belmont at the event.

engraving of the 1860 Ball at the Academy of Music for the Price of Wales

Although August was still held with a degree of suspicion by some in society’s inner circles, Caroline, outfitted in the latest fashions and accented by exquisite jewels, became its undisputed queen. With intelligence, warmth and a kind disposition to match her beauty, she would reign unchallenged for fifteen years. It is not unreasonable to suppose that a young matron in the crowd that night, also named Caroline (Astor), may have looked on with slightly more covetous eyes.

Caroline Belmont, 1870s

In Newport, the Belmonts commissioned architect George Champlin Mason to design an Italianate cottage on Bellevue Avenue for them in 1860 called By-The-Sea.

By-The-Sea

As in New York, the Belmonts raised the bar at the resort, with Mrs. Belmont ‘s demi-daumont carriage caused quite a stir amongst the summer colonists. In addition to the cottage, Belmont acquired Oakland Farm in nearby Portsmouth.

Caroline and August Belmont Jr. in the demi-daumont at By-the-Sea. Led by postillions on horseback, it allowed the carriage’s occupants to see and be seen unimpeded by a coachman blocking the view.

Closer to New York, August bought up farmland in North Babylon, Long Island, assembling a 1200-acre estate there. While their 24-room second empire house designed by architect Detlef Lienau (who was credited with bringing the second empire style to America) may seem modest compared to the lavish north shore mansions built in the following decades, it is important to note the estate’s significance as one of the first properties on Long Island to be maintained along the lines of a proper English country seat. In addition to the house, there was a greenhouse, conservatory, bowling alley, squash court, carriage house, stable for carriage horses, kennels, a bowling alley and squash court. It included a working farm, a herd of dairy cattle, hog pens and chicken coops, while game birds were raised for its private shooting preserve.

A photo of the mansion at Nursery Farm taken in the 20th century

By the 1870s Belmont would complain (brag) that the estate was costing him $50,00 year to run. A good deal that expense was from the estate’s raison d’etre, indulging Belmont’s passion for raising thoroughbred horses. Named Nursery Stud, its breeding and training facilities included separate stables, paddocks and a mile long practice track. A leading figure in thoroughbred racing and breeding, Belmont served as president of the National Jockey Club in America. After his friend Leonard Jerome opened new racetrack in the Bronx, he underwrote annual race there which would eventually become known as the Belmont Stakes.

Jerome Park, 1868

In the 1880s, Belmont would move Nursey Stud’s breeding operations to a leased farm near Lexington Kentucky.

In 1875 Tragedy struck the Belmont family when their nineteen-year-old daughter Jane died. Her death marked Caroline’s abdication from her throne, having no desire to take society’s center stage again after her period of mourning was over. That did not mean however, that the Belmonts totally withdrew from society by any means. In addition, as their other children came of age, they took up the mantle from their parents, assuming leading roles of society’s next generation.

The Belmonts in Costume for the 1883 Vanderbilt Ball

Their daughter Fredericka was the first to wed, marrying Samuel Shaw Howland in Newport in September 1877. The happy couple soon settled in a townhouse behind the Belmonts at Ten West Eighteenth Street.

Fredericka Belmont, circa 1875. photo: Museum of the City of New York Digital Collection

The Howlands also built a sporting estate near Mount Morris New York named Belwood, where, like his in-laws, Samuel established a stud farm.

The main house (top) gate house and main barn at Belwood

August Belmont Jr., who worked for the family firm alongside his father was next, marrying Elizabeth “Bessie” Hamilton Morgan on November 29, 1881 in New York City.

Mr and Mrs August Belmont Jr atop their coach (front) photo: Museum of the City of New York Digital Collection

Purchasing an estate in Hempstead which they named Blemton Manor (an anagram of the word Belmont), they began raising champion fox terriers there, and August jr. became president of the American Kennel Club in 1888.

While eldest son Perry eschewed the world of finance and became a lawyer, he followed his father’s path into the world of politics. Elected to the US House of Representatives, he served between 1881 and 1888, when he was appointed US Minister to Spain. He remained a bachelor, keeping a place in Washington, and using 109 Fifth Avenue as his New York residence.

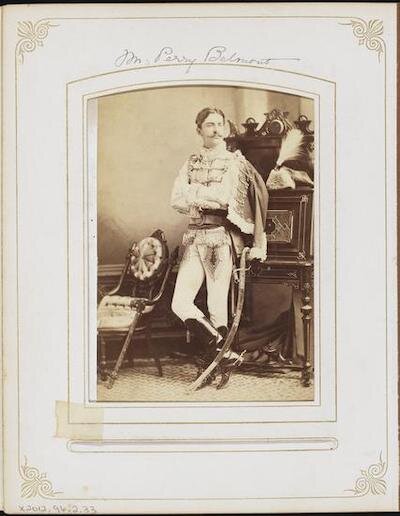

Perry in Costume for the Vanderbilt Ball, 1883 photo: Museum of the City of New York Digital Collections

Oliver presented a bit more of a problem for his parents. Showing little interest in the family firm, he initially followed in the footsteps of his mother’s kin, enrolling in the United State Naval Academy. After serving briefly as a cadet midshipman he resigned in 1881, and gained a reputation as a bit of rake, with a weakness for drink, gambling and the ladies. In 1882 he proposed to a popular young debutante Sara “Sallie” Swan Whiting. August and Caroline weren’t initially receptive, believing him too immature for the responsibilities of marriage. They sent him to Germany to work at one of the Rothschild banks, but when reports of his licentious behavior there reached them, they acquiesced to the marriage, hoping Sallie might be a steadying influence.

Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont

Oliver and Sallie were wed on December 27, 1882 in Newport at Swanhurst her family’s villa, with the leading members of the summer colony in attendance. The couple sailed to Paris for an extended honeymoon, where they were to be joined by Sally’s mother and two sisters several weeks later. The following spring, a short item distributed by the Associated Press appeared in newspapers across the country.

The statement masked a darker truth. Soon after Sallie’s family joined them in Paris, Oliver fell back into his dissolute ways. He began drinking absinthe, which made him violent, and would go out carousing for days at a time. He eventually disappeared altogether, spotted weeks later in Bordeaux with a French dancer. Discovering she was pregnant, Sallie departed for America in April. When Oliver got wind of it, arrived stateside a few weeks later. If a reconciliation was hoped for the part of the two families, it was for naught. Oliver stayed in New York and made no immediate plans to go to Newport, where Sally was living. It was then made clear that she would not receive him there if he did.

When he did finally go to Newport, it was to set up residence at Oakland Farm, leading society tongues to note as a Rhode Island resident it would be much easier to obtain a divorce than in New York. Their daughter, Natica Caroline Belmont was born September 5, 1883. Oliver was not allowed to see her and eventually denied paternity. By the end of the year, it was open knowledge that the young Belmonts were heading for divorce. At the time, divorce was highly scandalous and almost universally more damaging to the female partners reputation. In the high-profile case Oliver and Sally’s marital breakup, its reverberations rippled beyond their immediate families giving rise to a very public feud.

The truth was probably far less extreme. While undoubtedly there had been tension between the two families, the story was most likely planted by someone connected to Mrs. Astor in order to reinforce her position of Queen of Society as unassailable. While socialites could not stoop to acknowledge the press or give interviews, as the celebrities of the day, they were very aware of the power the media wielded. Leading hostesses often had discrete backchannel connections with newspapers in order to support their ambitions and shape public opinion. Despite the supposed war, when the New York Times covered Carrie Astor and Orme Wilson’s wedding in November 1884, prominently listed amongst the top of the guest lists was every member of the Belmont family and their spouses (with the unsurprising exception of Oliver).

In January 1887 tragedy stalked the family again, when late one night their youngest son Raymond died after accidentally shooting himself in the head while doing target practice in the basement of 109 Fifth Avenue. Caroline withdrew even further from society. Interestingly, as its former queen, her rare appearances at an event, such as a dinner given by Mrs. Ogden Mills in 1890, were used to underscore its exclusivity and importance (in this instance, it was probably no mistake that Mrs. Mills was seen as a leading rival for Mrs. Astor’s throne).

Coverage of the Mills dinner. Illustrating how small the social fishbowl was, two other women mentioned, Mrs. Vanderbilt and Mrs. Sloane, would each go on to marry one of Caroline’s sons

In 1890, August still active and healthy at 63, caught a cold while judging the annual horse show at Madison Square Garden. The doctors didn’t believe it be serious initially, but It rapidly progressed to pneumonia. Belmont died on November 24, surrounded by his wife and surviving children. In his will he instructed that his horse breeding operations be shut down and the stock sold. He left Caroline all their personal possessions, 190 Fifth Avenue, By-The Sea, as well as a trust that would grant her an income of over $50,000 (the equivalent of roughly $1.7 million today) a year. He also created a trust for Fredericka, guaranteeing her an annual income. The remainder of his estate, estimated at $8-10 million, was to be split between his three living sons.