Gilded Age Cottages of Cooperstown, Part 2 (1900-1915)

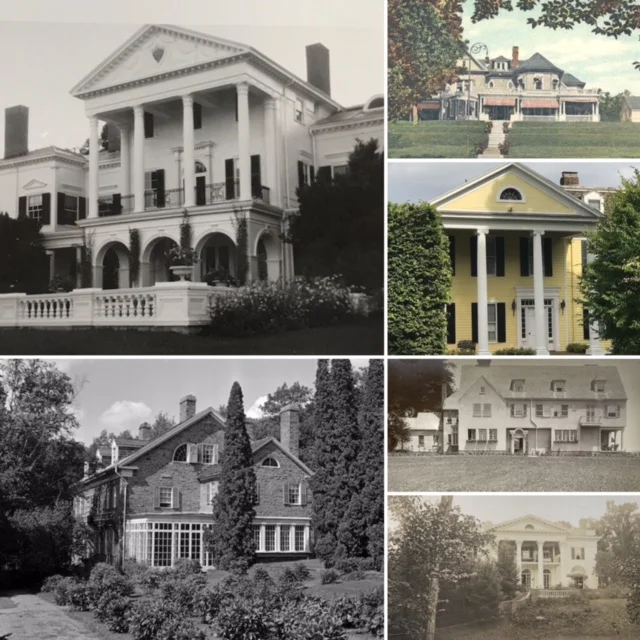

The dawn of the twentieth century saw a marked change in the style of summer cottages built in summer resorts by the era’s elite (to see my previous post focusing on cottages built in the nineteenth century, click here). While homes continued to be built in the shingle and colonial revival styles, the irregularity and exuberance of Queen Anne and Victorian styles gave way to symmetry, classicism,interpretations of the great houses of Europe, and early American styles . While many of the larger, splashier resorts took cues from the Beaux-arts, French chateaux, or the Italian renaissance for reference, Cooperstown’s summer colonists tended to favor lower-key precedents, such as Georgian England or America’s Federal period, in keeping with its reputation. To follow are some examples from the early twentieth century (as well as a few post-gilded age ones thrown in for good measure).

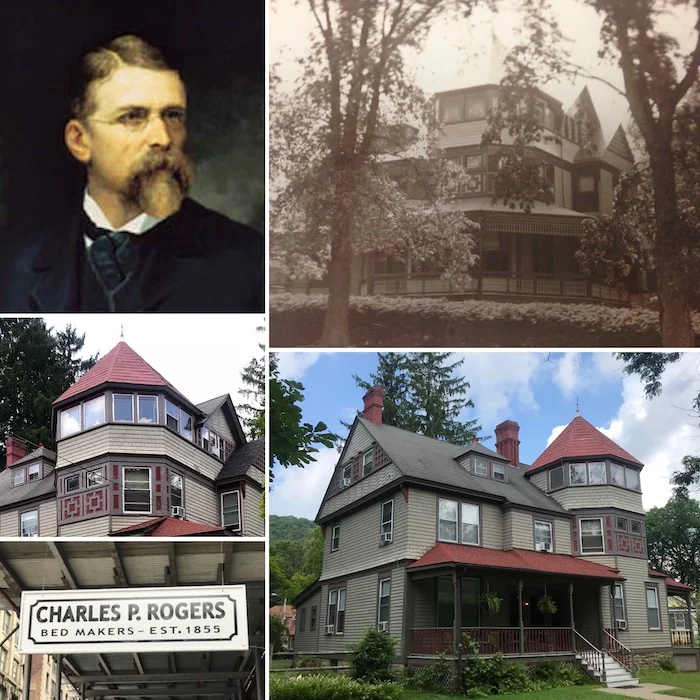

Uncas Lodge

Uncas Lodge, perched above Three Mile point, was completed in 1901 for Simon Uhlmann on the farm he purchased the August van Horne in 1899. A hops dealer with interests in several other businesses, (serving as a director of the Hinckel Brewery in Albany and the Brooklyn Elevated Railroad) he often entertained large numbers of business associates there. The comfortable shingle-clad, colonial revival residence is a good illustration of the bridge between the earlier Queen Anne styles and the restraint found the twentieth century ones.

photo: New York State Historical Association Library, Cooperstown, New York, Florence Ward Local History Collection

In 1904, Uhlmann sold Uncas Lodge to another brewer, Adolphus Busch of St Louis.

Mr. Busch riding his pet baby elephant around the grounds of his home. photo: New York State Historical Association Library, Cooperstown, New York, Florence Ward Local History Collection

The estate has been owned by the Busch family and their descendants ever since.

A home built by a Busch descendant on the the property in 2002

Though over the past hundred years they have increased their landholdings and built several other substantial homes on the property, Uncas Lodge remains the heart of the estate, well cared for and beloved by the family.

Ringwood Manor

Arthur Ryerson, scion of a Chicago steel fortune, had a large English arts and crafts style cottage built at the head of the Lake in 1901. Named Ringwood Manor, the large but comfortable home became a favored residence for the Ryerson family, who also maintained a residence on the Main Line in addition to Chicago.

View of the garden from the front door

Unfortunately, the family’s name is best known today for the double tragedy that befell them in April of 1912. While traveling in Europe, the Ryerson’s received word that their oldest son had been killed in an automobile accident in Haverford. The grief-stricken Arthur, his wife Emily, along with their daughters Emily and Suzette and son Jack booked passage on the next steamship headed to New York from Cherbourg, the RMS Titanic. Arthur Ryerson lost his life in the sinking, and his son Jack was almost denied entrance to a lifeboat because he was thirteen at the time, too old to be considered a child according the officer in charge. The Ryerson family donated the estate to the Episcopal Church in the 1960s.

Living Room today

Dining Room Today

After operating Ringwood as a camp and conference center named Beaver Cross for several decades, the church sold the property to an investment group roughly ten years ago, who have been trying to find a buyer to rehabilitate or restore the property. At last word, it was still on the market.

View of the house several years ago

Mohican Manor

photo: New York State Historical Association Library, Cooperstown, New York, Florence Ward Local History Collection

In 1897 Samuel Strong Spaulding of Buffalo purchased a large parcel of land from Leslie Pell Clarke just to the south of Cary Mede. Mohican Manor, Spaulding’s 150 foot long federal-style mansion completed in 1901 was one of the largest and most elaborate built on Otsego Lake during the era.

In addition to the mansion, Boston architect E A P Newcomb also designed a handsome boathouse and carriage house for the property. A series of semi-circular stepped terraces leading down from the mansion to the lakeshore, formal gardens, and a meticulous farm complex made the estate one of the showplaces of the region.

photo: New York State Historical Association Library, Cooperstown, New York, Florence Ward Local History Collection

Spaulding’s heirs sold the property to the Clark estates, in the 1940’s. After serving a convalescent home for soldiers after World War 2, the Clark Foundation used the estate as the Mohican Reading School in the 1950s and 1960s. By the 1970s however, maintenance and taxes on the large, now unused building proved too burdensome.

View down the Hallway

The mansion’s contents, architectural and building elements were auctioned off in August of 1979, and it was razed shortly afterwards.

Advertisement from the auction in 1979

Though undoubtedly a loss, this at least allowed the property, along with some of the gardens and outbuildings, to remain intact, and undeveloped today and for the foreseeable the future.

The Orchards

J A M Johnston began construction of the Orchards in 1901, on a large parcel of land bordering Lake and Pine Streets. The handsome white mansion with its monumental Corinthian portico was officially opened in 1903 with a coming of age party for Stephen C. Clark. To accommodate the 300 guests, a temporary ballroom and dining room were constructed as wings on either side of the main block of the home. These temporary additions were so skillfully executed many guests assumed they were part of the permanent fabric of the home.

photo: New York State Historical Association Library, Cooperstown, New York, Florence Ward Local History Collection

Though it stood within the village, the skillfully planted expansive grounds lent it the feel of a country home.

photo: New York State Historical Association Library, Cooperstown, New York, Florence Ward Local History Collection

The Gardens below the terrace and a pool shaped to resemble a pond added to the effect.

photo: New York State Historical Association Library, Cooperstown, New York, Florence Ward Local History Collection

After Johnston’s death in 1914 his son, Waldo C Johnston’s family occupied the house until the 1940’s, when the house was razed and the property was subdivided into seven building lots. One of the homes built on the former site of the mansion supposedly incorporates the Orchards kitchen wing, which survived.

The Hawthorns

The Hawthorns began its existence well before the Gilded Age, as a somewhat typical Greek revival house similar to examples that can be found all over the Otsego County before Mrs. Stephen G Browning purchased it in the early twentieth century.

Mrs. Browning, née Charlotte Prentiss , a Cooperstown native, had previously owned a handsome brick townhouse on Main St. that she had grown up in. Now widowed and spending her winters in Chicago with her married daughter, she set about transforming Hawthorne Cottage into a proper gilded age summer cottage. In 1913, she had local contractor Fayette Houck substantially alter the home’s interiors, enlarge an existing wing to more than double the size of the house, and add an ionic columned portico to the main block.

Mrs. Browning occupied the Hawthorns every season until her death in the 1930s. Well-maintained and modernized over the years (most recently by Lady Juliet Tagdell) serves as a good example of an earlier village house adapted to the needs of the Gilded Age summer colony.

Fynmere

In 1910, James Fenimore Cooper (grandson of the novelist), commissioned architect Frank Whiting design a country home for a large parcel of land he owned on Estli Avenue. The resulting handsome Georgian Revival mansion built of native fieldstone fit so well into its surroundings, one might mistakenly assume it had stood there for a hundred years.

Several years later, Cooper engaged architect Charles Platt to plan alterations to the house and landscape, who collaborated with Ellen Biddle Shipman to design the gardens (in her first major professional commission).

The Cooper family donated Fynmere to the Presbyterian Church in 1952 to be used as a home for retired clergy.

The church eventually found the maintenance and upkeep on the estate too costly, and gave it back to the family who reluctantly had the home razed in the late 1970s. The intact grounds with their stone terraces overgrown plantings and charming garden house serve as a hauntingly beautiful reminder of what was once there.

The Gardens in the late 20th century

Post-Gilded Age Honorable Mention

Though cottage building slowed after World War 1, the new homes which were built tended to blend seamlessly with those that came before them, often in the same Georgian revival or restrained colonial revival styles.

Fenimore House

Many people mistake the Fenimore House (now a museum) for a Gilded age mansion, but in reality, in was constructed in 1931 during the Great Depression for a member of the Clark family, who donated it to the New York State Historical Association in 1948.