The Eustis Estate Museum, a Gilded Age Treasure outside of Boston

In Boston for an overnight visit recently, Brendan and I were looking for someplace to visit on the drive back home. Our host suggested the Eustis Estate Museum, a place we hadn’t heard of before. That is probably due to the fact that the mansion and eighty-acre grounds, located about 10 miles southwest of downtown Boston in a surprisingly bucolic section of Milton before were only opened to the public by Historic New England fairly recently, in June 2018. It was definitely worth the trip.

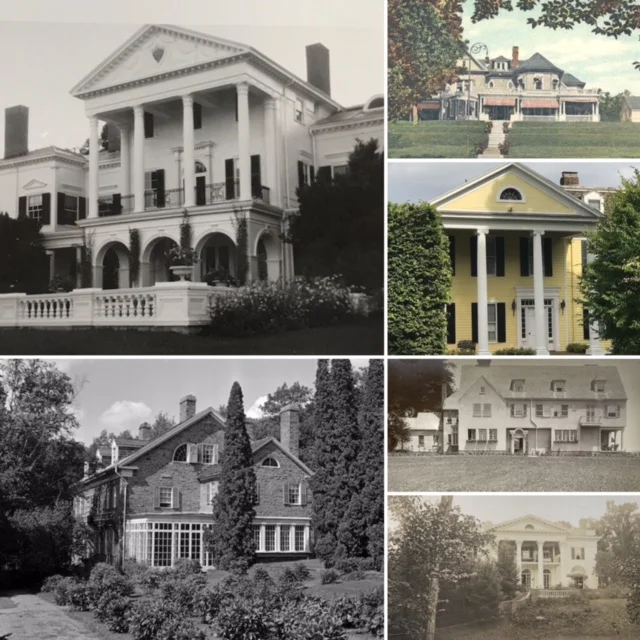

The history of the estate begins in 1878, when W. E. C. Eustis and his wife, née Edith Hemenway, were given 250 acres by Edith’s mother, Mary Hemenway to build a house upon. The property adjoined her large estate to the south and conveniently, Eustis’s parents owned a neighboring estate to the north.

Renowned Boston architect William Ralph Emerson was called on to design the new home. Sometimes dubbed the “father of the shingle style in New England ” he is perhaps best known for the cottages he designed on Mt Desert Island, in Newport, and other popular east coast resorts.

Emerson’s Design for Redwood Cottage in Bar Harbor, ME

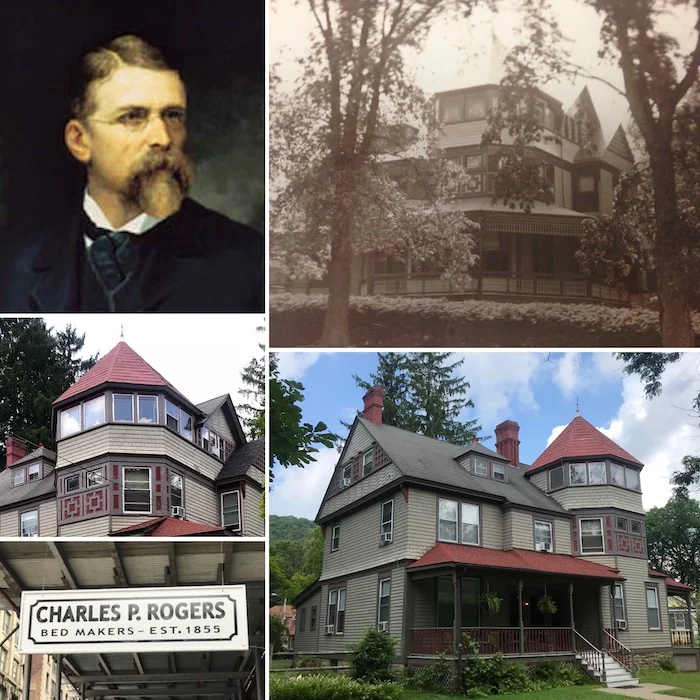

He also appears to have been the “go-two” architect for the Eustis and Hemenway families for a period. Emerson had transformed Mary Hemenway’s residence on her Milton estate the year before, and eventually executed no less than five projects for the extended clan.

Emerson’s work on Mary Hemenway’s home the prior year transformed it from a colonial home into the “modern” mansion seen above

We entered the estate from Canton Avenue, passing alongside this interesting rustic fieldstone gatehouse and adjoining carriage house and stable built in 1892.

Impressive as it was, it was soon eclipsed by the site of the formidable mansion looming on the hill ahead.

The entrance façade of the house is dominated by an arched porte cochere supporting a gabled extension above.

Historical photographs show lush vines creeping up the walls, but I am happy they were removed in the mid twentieth century.

It allows for an appreciation of the interplay between the random color patterns formed by stones of various hues and the geometric patterns of multi-colored bricks along with the painted wooden elements of the house.

The porte-cochere’s arch is repeated in the recessed porches along the western side of the house,

furnished with rocking chairs, to encourage visitors to sit and enjoy the view.

It is not just the use of materials that gives the house its remarkable sense of plasticity. The structure’s planes are interrupted by stepped rises alongside and atop the arches, bays projecting from walls, which contrast with slightly recessed sections, the roofline is punctuated by dormers and gables.

Together they create a form that almost undulates, with interest and variation from every angle. Even the façade of the service wing gets a similar treatment.

I admired the numerous balconies, especially one on the third floor, in front of a glassed-in dormer bisected by a chimney, allowing for multi-seasonal admiration of the vistas below.

We entered the house through a small vestibule with double doors inset with stained glass, into the large living hall beyond.

My attention was initially drawn to the elaborate fireplace to our right, featuring molded terra cotta and carved wood. It is set off by a large arch covered in gold-leaf (a touch that literally puts the “gild” in this “gilded age” mansion).

Opposite the fireplace, the grand staircase begins its three-story ascent, soaring the entire height of the structure.

Stained glass windows set in dormers high above help illuminate the striking views from each landing as we marched upward.

Other public rooms on the first floor include a handsome dining room and the large and small parlors. The large parlor was where the family generally received guests.

Tiles set in the floor in front of the rooms fireplace were warmed by a radiant heating system, just one example of the state-of the art technical features of the house when it was new. The stuffed peacock on the mantel, while not origina, is a nod to the mansions interiors, which reflect the aesthetic movement.

The aesthetic movement loosely defined an era in the fine and decorative arts that lasted roughly between 1860 and 1890. It was rooted in, amongst other things, a rejection of the previously dominant styles inspired by classical and European historical in favor of nature. It was strongly influenced a fascination with Japan (and the far-east in general) that came after Commodore Perry opened the country up in 1859.

This mantel in the small parlor features an opening inspired by an Asian Moon Gate, and till decorated with birds and cherry blossoms

Its popularity took off after the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, two years before the Eustis mansion was built. Some of the readily identifiable elements associated with aesthetic movement found within the mansion include;

Blue and White Porcelain

The prominent use of flowers, and birds in decoration.

and ebonized furniture

While the style of this chair is technically Italian Renaissance, its dark color sort of fits the theme

After exploring the main rooms upstairs and down, we visited the first floor service wing, reached via corrider to the left of the front door. My favorite part of this wing was seeing this little phone booth, a reminder of a time when people considered phone conversations private afffairs. That is one gilded age custom I wish would make a come back!

In addition to the requisite butlers pantry,

storage areas for china and silver,

call buttons and speaking tubes to summon the servants,

the large kitchen featured both a nineteenth century stove and a modern dishwasher.

The juxtaposition serves as a reminder that the Eustis family continuously lived in the house from the time it was built, until 2014, two years after Historic New England purchased the house and eighty acres from them in 2012. While the organization has definitely done an admirable, state of the art restoration, the family’s love and exemplary stewardship of the place is very evident.

Restoration and interpretation aside, Historic New England should be applauded for achieving the delicate balance of blending a historic house museum with gallery and exhibit space.

They have hit just the right note of reverence coupled with accessibility as well. Guests have plenty of places to sit, can read books in the library, and learn as much or as little about the fascinating place as they wish from digital kiosks or helpful guides.

This spirit continued outside the mansion, where a contemporary sculpture show encourages people to explore the grounds. While this silver polar bear grouping might bother a purist – who says historic houses can’t have a little fun too?

For more information on the Estate and its history, please visit its website, which has plenty of interesting information