You Might Be Surprised To Know How Much of Cooperstown Was Built on a Dime (Novel, that is): The Legacy of E F Beadle

“Mothers of River City!

Heed the warning before it's too late!

Watch for the telltale signs of corruption!”

“Is there a nicotine stain on his index finger?

A dime novel hidden in the corn crib?”

The inclusion of the Dime Novel as a sign of “Trouble” in The MusicMan is a light-hearted take on what was once perceived as a very real threat to the moral fiber of our nation’s youth. Ministers across the land warned that exposure to them was directly linked to adolescent criminality. Reformer Anthony Comstock, founder of the “New York Society for the Suppression of Vice” claimed dime novels had a “demoralizing influence upon the young mind” by arousing sexual thoughts. The Tribune blamed them for many types of juvenile delinquency (including guns in schools), informing its readership their focus taught that "violence and trickery and immorality are manly, and that the character to be admired is the bully and ruffian who knocks everybody about, and cuts throats right and left.” Yes, many believed the Dime Novel was a scourge to society.

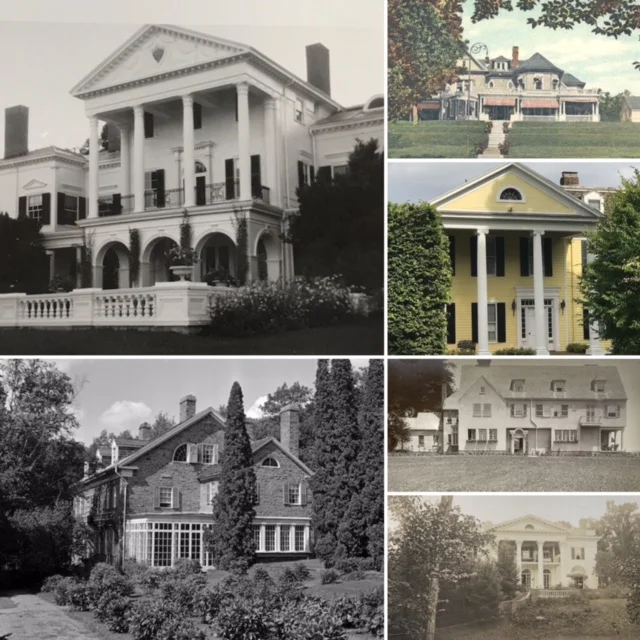

It might be startling then, when admiring the oh-so respectable looking late nineteenth century homes gracing Pine Boulevard and Nelson Avenue in Cooperstown, to learn that many owe their very existence, at least in part, to this “disreputable’ early form of pulp fiction.

And how are they connected?

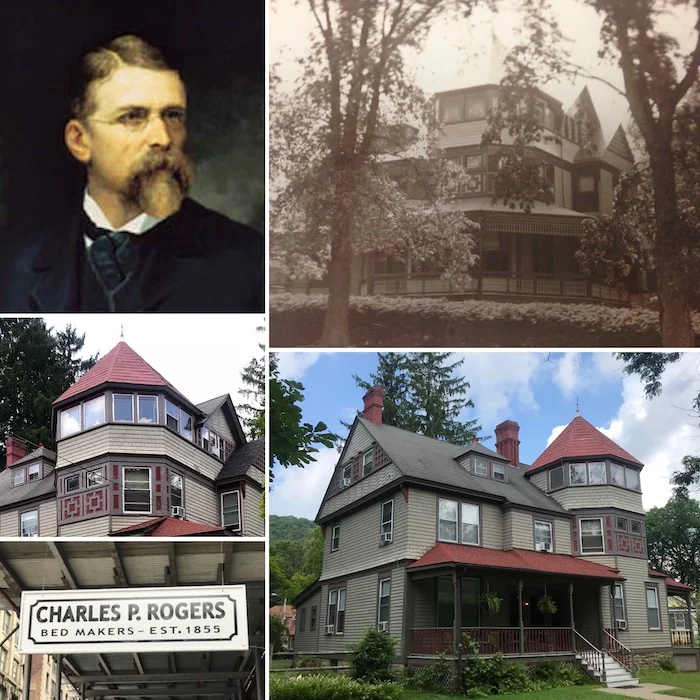

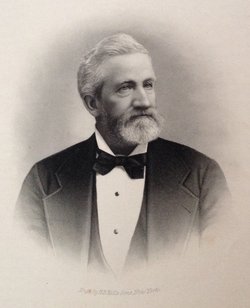

Through Erastus Flavel Beadle.

Born in nearby Pierstown in 1821, Erastus apprenticed with the Cooperstown publishing firm of H & E Phinney in 1838. The industrious young man later moved to Buffalo where he worked as a stereotype. Joined there by his brother Irwin, the ambitious duo had set up their own stereotype business by 1850, moving it to New York City in 1858.

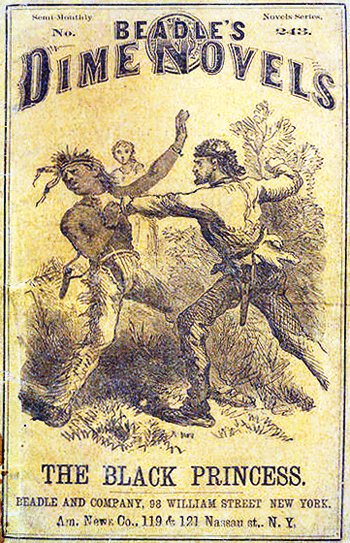

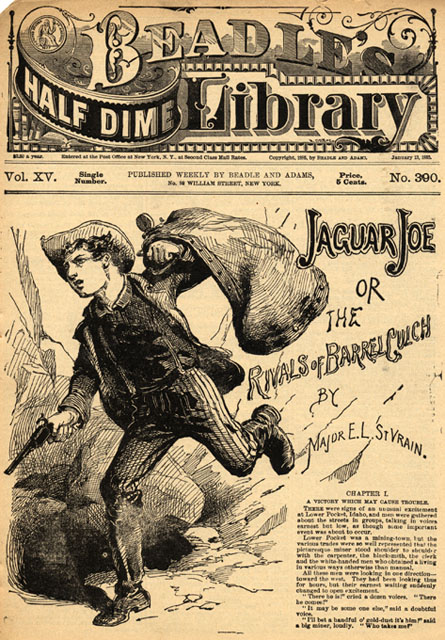

The firm (later named Beadle & Adams) developed a series of booklets on a wide variety of subjects, from cooking to baseball. Noting the popularity of serialized stories in newspapers, they experimented with adapting their booklets as a vehicle for serialized works of fiction. The first novel they printed, advertised as “a dollar book for a dime”, was a runaway hit, selling more than 65,000 copies in the first few months.

The fast-paced sagas, often featuring Western adventurers, backwoodsmen, and hunters, especially appealed to young working class men and women. While the Civil War initially slowed sales, Union troops soon proved a voracious readership. Looking for a new market in the 1870s, they believed a nickel price might make the novels more accessible to children. The firm developed a line of “half dime” novels featuring stories written specifically for boys, and soon America’s youth was hooked!

Despite their detractors, Dime Novels primarily featured morally upright storylines. Bad guys were captured and punished in the end, while good guys were brave, chivalrous, and patriotic, and the attractive damsels in distress were chaste and pure. Critics seem to have been motivated more by an inherent distrust of anything embraced by youth rather than its actual content (a pattern of looking at pop culture that ironically repeats itself to this very day!).

While there other publishing companies were doing the same thing, Beadle and Adams was by far the most successful. His brother Irwin actually came up with the concept, but Erastus a shrewd businessman and marketing genius, ended up getting most of the credit for their success (and the profits), making him a wealthy man.

Marcy Hall: Courtesy of the New York State Historical Association (NYSHA) Library, Cooperstown, New York, Florence Ward Local History Collection (Chestnut)

Luckily for Cooperstown, his attention turned towards the village where he got his start in business. The Beadle family began summering at Marcy Hall, a handsome stone residence located just south of the village. By the early 1880s they were ensconced in Glimmerview, an imposing Italianate pile on Lake Street which Beadle substantially enlarged.

Glimmerview, Courtesy of the NYSHA Library, Ward Collection, 54 Lake (Glimmerview)

Not content to sit back and enjoy the view of the lake from his summer home, the restless Erastus began buying buildings around the village. Some he resold, others he rented out, but in nearly every instance, he made significant improvements to them. In addition to local landmarks such as the the former County Courthouse (later sold to Alfred Corning Clark), he also purchased a row of workman’s cottages on Pioneer Street, renovating them to create affordable housing for those of modest means.

In April of 1882 Beadle purchased a large parcel of land on Pine Street (then the western outskirts of the village), acquiring an additional 7 acres to the south and west soon thereafter. By September a wide “suburban” street named Nelson Avenue had been laid through his property, connecting Main and Lake Streets. Named after Justice Samuel Nelson, one of Cooperstown’s most illustrious residents, Erastus envisioned a fashionable middle class neighborhood rising up on the large building lots he had begun to lay out along the avenue. To encourage development and perhaps “set the tone’ of the neighborhood, he also planned on building what we now refer to as “Spec Houses” on some of the lots. In 1883 the first two lots were recorded sold to local residents, who had new homes upon them by the next year (still standing today at 4 and 6 Pine Boulevard). After that, things really began to roll. Between 1885 and 1886 at least seven more building lots were solid addition to two new speculative residences he had constructed.

Cherry Hall, Nelson Avenue

One, named Cherry Hall after its solid cherry interiors, was sold to J. W. Fowler for the handsome sum $7,000. Coincidentally, earlier that year Erastus had purchased Fowler’s once grand, but by then rather shabby looking residence on Pine Street, which was adjacent to some of Beadle’s other properties.

JW Fowler residence in better days, Courtesy of the NYSHA Library, Ward Collection (8 Pine)

Whether this was a move designed to protect the value of his real estate investments, or simply a new opportunity to build, Beadle had the existing gothic revival structure razed, and a large new house named “Overlook Cottage” soon rose in its place.

Overlook Today

Beadle soon leased it as well as the neighboring “Manhattan Villa” he had recently built, to families from New York who formed part of Cooperstown’s growing summer colony.

Manhattan Villa

Erastus’s efforts began to garner him attention and praise locally. In May of 1887, the Freeman’s Journal dubbed him “Cooperstown’s energetic property improver”. Quite a feat considering that during the same period Erastus was not only running his publishing business in New York City, but was also plagued by health issues and had several family tragedies to deal with. During the summer of 1881 his son in-law passed away at Marcy Hall. Severe asthma forced Erastus to spend part of each winter in Colorado (the silver lining may have been his widowed daughter’s subsequent marriage to Denver Banker E L Raymond in 1886). In December of 1885 the papers somberly reported that the Beadles had brought their son Irwin, gravely ill with typhoid, up to Cooperstown to spend his last days. Happily, Irwin’s health improved and he eventually recovered.

1889 began like any other year for Erastus, buying a house in January (built on one of his Pine Street lot he had sold a few years earlier) with the intention of remodeling it. A severe asthma attack sent him to Colorado later that month, earlier than expected. Although his wife’s health had been of concern for some time, her unexpected death in May dealt Erastus a major blow. He sold his business interests in New York and decided to retire to Cooperstown fulltime. Though grieving and forced spend a good deal of that summer at the seashore for his own health, Erastus’s inherent energy wouldn’t allow him remain inactive for long. On October 11th, the Freemans Journal noted that the renovations of the cottage he purchased in January were nearly complete, he was eager to begin work on a newly acquired building on Main Street (today housing the Mohican Club). The paper went on to state “few men have done more in the last half century to improve the village” . In November he donated a plot of land on Nelson Avenue to be used as the future site of The Thanksgiving Hospital, before departing Cooperstown to spend the winter in Colorado.

His return in February of 1890 marked a new period of intense activity, initially focusing on improvements to some of the buildings he had recently acquired, including the Nichols mansion on Fair St.

Nichols Mansion

He had also discovered a new hobby, installing an elaborate ‘pheasantry’ on the grounds of Glimmerview and filling it over the next several years with all sorts of exotic fowl. Towards autumn, ground was broken for a new cottage on Pine Boulevard, which was finished towards the end of 1891, along with three other new homes on Pine Street and Nelson Avenues. Although it might be hard to tell by looking at them today under later cosmetic alterations and additions, the houses Erastus built had a distinct character.

Although they employ some of the standard decorative elements and surface treatments inherent to the stick and shingle styles then in vogue, he avoided the excessive and ostentatious ornamentation often found on Victorian homes of that era. They usually featured large third floor dormers or towers, often situated to allow a view of the liken the distance. Looking at the ealry views below of 2 Pine Boulevard, Overlook Cottage and 33 Nelson Avenue, with there not notable lack of froufrou gingerbread trim, one could venture to say that Beadle's pared-down taste might be described as minimalist for that time!

Courtesy of the NYSHA Library, Ward Collection, 2 Pine Courtesy of the NYSHA Library, Ward Collection, 8 Pine Courtesy of the NYSHA Library, Ward Collection, 33 Nelson

When Erastus F Beadle died in December of 1894 at the age of 73, papers near and far lauded his innovations to the publishing industry, the fortune he amassed, his philanthropy and civic-mindedness. Nowhere were his achievements more celebrated than in Cooperstown. The Freemans Journal noted that not only did he make new buildings, but was constantly buying others to make more beautiful. There was scarcely a street in the village that he hadn’t positively impacted in some way, and one of them, Pine Street was officially renamed Beadle Avenue in his honor.

For a name made famous in part by the ephemeral nature of pop culture, it might be no surprise that collective memory can be short and renown can be fleeting. Dime Novel readership was already in decline by the time Beadle sold his interest in his firm, inevitably replaced by successive waves of new cheap entertainment including cartoons, radio, movies, and television ( within several decades after Beadle's death, dime novels were remembered nostalgically as wholesome and harmless entertainment). The year before he passed away, the Thanksgiving Hospital regretfully decided to give back the land he donated to build a new hospital on as no one could ever imagine public sewer lines extending all the way out to Nelson Avenue. Erastus’s reputedly large fortune turned out to be not so large, consisting primarily of his Cooperstown real estate (he owned no less than eight dwellings there at the time of his death), which his family began to sell off, one by one. By the time his former mansion Glimmerview was razed in the 1940s, it was more associated with the Zabriskie family who had bought it from his estate (click here to see a youtube video compilation taken during their time there). Within two years of his death, petitions were circulated to change Beadle Avenue back to Pine Street (later Boulevard), and eventually the town agreed. A century later, the name E F Beadle is often not recognized, even in the village where its shadow once loomed so large. Fortunately, dozens of gracious homes along upper Main Street, Nelson Avenue and Pine Boulevard stand as a solid, permanent tribute to E F Beadle’ s vision and foresight.