Downsizing, Vanderbilt Style Part One: The Story of Four Sisters.

Imagine you were living in the 1880’s, ensconced in a grand mansion located on the most fashionable stretch of 5th Avenue. Given to you by your late father, he also left you a personal fortune of 10 million dollars; half outright, and half in trust. Looking out your windows, gazing out your windows, you are surrounded by the equally grand homes of relatives and neighbors, all members of the upper echelon of New York society. Wealthy, secure, and comfortable, you couldn’t be blamed for thinking that your life would never change.

But change was coming. Drawn by the fashionable nature of the neighborhood which your very name helped establish, swanky hotels began to make an appearance. Retail establishments catering to the carriage trade soon followed; department stores and office buildings in turn. As more commercial buildings went up around you, real estate values began to climb higher and higher (along with the annual taxes on your property). One by one friends and neighbors, lured by the astronomically high prices offered by commercial developers and assaulted by ever increasing crowds and traffic on the streets, begin to sell their homes and move farther uptown. Looking out your windows, you’re now confronted by a sea of tourists, shoppers, and office workers on their lunch break swarming around your home. What was a self-respecting society matron to do? If you were one of the four Vanderbilt sisters, you had a couple of choices, ultimately influenced, if not dictated by, the type of marriage each made.

Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard

Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard, the eldest of the four sisters was also the first to decamp from her midtown mansion. Margaret’s husband, Elliot Fitch Shepard, was by all accounts, not a beloved figure amongst his in-laws, or many other people for that matter. Strict, arrogant, religious, and conservative, he kept Margaret and his children under his dour thumb. When he died in 1895, it was discovered he had also effectively spent all her money not held in trust on failed business ventures and runs for political office. Margaret, in the process of constructing an impressive six hundred acre Westchester estate (today the Sleepy Hollow Country Club), suddenly found herself pressed for cash. She had no choice but to sell her home at 2 West 52nd Street.

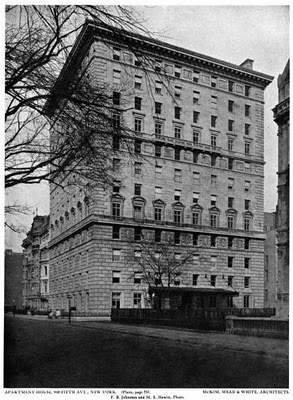

Initially she moved just down the street to the Belgravia Apartments, located on thesite where Saks Fifth Avenue stands today. The Belgravia was one of Manhattan’s first luxury apartment buildings, offering the wealthy a low maintenance, less costly, but respectable alternative to owning a house in town. Ironically, her husbands death and forced sale of her townhouse granted Margaret a new lease on life, allowing her a degree of independence to travel freely and enjoy time with her grown children. She later bought another apartment in the McKim Mead and White designed 998 Fifth Avenue.

It was there that she died suddenly of a heart attack in 1924, the first of the sisters to go.

Emily Vanderbilt Sloane White

When Margaret decided to sell 2 West 52nd street, she didn’t have to look far for a buyer. The purchaser was her next-door neighbor and younger sister, Emily Thorn Vanderbilt Sloane. Emily Sloane enjoyed a charmed existence in comparison to Margaret. She married William Douglas Sloane, who was active in his family’s famous home furnishings and furniture business, WJ Sloane. While much of old guard New York society made a point to look down on those “in trade”; so charming was the couple (along with their children) soon not only were they safely ensconced in, but eventually became leading members of the fabled “Four Hundred”. Although Emily was known for a rather lighthearted attitude towards society, she still followed all of its rituals and needed a larger stage for entertaining. She combined her sister Margaret’s house with her own, creating a mansion nearly equal in size and scale to her father’s on the southern half of her block (now owned by her brother George).

2 West 52nd St

When William Sloane died in 1915, he left Emily richer than when he met her. In 1920 Emily married for a second time, to former Ambassador Henry White. Emily White continued to enjoy life to the fullest, spending the summers at Elm Court, her 93 room shingle style cottage in Lenox (still owned by her descendants, who run it as an inn), returning to New York for the social season. She was a fixture at the Opera (owning a box in "the Golden Horse Shoe" with her sister Florence), while hosting musicales and large debutante parties to launch granddaughters and niece's into society at her mansion in the early 1920’s. By the mid-1920’s however, she could no longer ignore the changes going on around her city home. Her brother William K Vanderbilt's mansion stood right across 52nd Street. After his death in 1920, His famed chateau was soon demolished, replaced by a pedestrian six-story office building that greeted Mrs. White each time she went out her front door. Although her daughter Lila Sloane Field still occupied one of the Marble Twins across from her on Fifth Avenue, right next door, the mansion once occupied by the Morton Plants, was now a shop (albeit Cartier)!

Cartier with Emily White's daughter's home seen to the right

With her own children and many of her of grandchildren grown up, many with large mansions of their own, she also now longer needed a "palace". Emily sold her mansion to developers in 1925. Demolished in short order, the famed retailer DePinna soon occupied the site. Emily did not move into an apartment building however. Instead, she bought the former Livingston Beekman residence at 854 5th Avenue, facing Central Park.

While smaller than her former home, the 25 foot wide Warren and Wetmore designed mansion was more than scaled for gracious living. With no financial worries, Emily shuttled between there and Elm Court for the next two decades, maintaining her homes and lifestyle as if the Great Depression and World War Two never occurred, up until her dying peacefully at her Lenox estate in 1946. Her former home still stands on Fifth Avenue, currently the home of the Serbian mission to the United Nations. It’s in need of a cleaning, but still elegant.

Mrs. Hamilton McKown Twombly

The next sister, Florence Adele, married Hamilton Mckown Twombly. A shrewd investor and astute businessman, Hamilton often advised his father in-law and Florence’s brothers on the management of their railroads and investments. When he died in 1910, not only did he live Florence richer than her found her, her left her richer than most of her family, no easy feat. With an income estimated at several million (pre-income tax) dollars a year, Florence regally entertained the cream of society at Florham, her elaborate country estate in New Jersey, (now the campus of Fairleigh Dickinson University), her Newport cottage Vinland (now part of Salve Regina College), as well as her New York home at 684 Fifth Avenue given to her by her father.

684 Fifth Avenue. Immediately adjacent to the left is 680 Fifth Avenue

She remains a legend to this day as one of the most formidable grande dames in New York history, known for rigidly maintaining the high standards of living, style and etiquette that had slipped elsewhere, as well as for her sharp tongue, form which even her family was not immune. Once, while sitting on the veranda of her sister Lila’s home in Vermont, she complained of feeling a chill. When her sister's butler appeared immediately, offering her one of Lila’s own shawls to wear, she supposedly took one look at the garment, then her sister, and snapped, “I’m not THAT cold!”

Another tale concerns a guest attending one of Mrs. Twombly’s legendary Florham weekend house parties over a Labor Day weekend. Finding his bags packed in the great front hall ready for his departure late Sunday afternoon, he asked a footman why, explaining that he since it was a holiday weekend, he had assumed he would be staying until Monday. The footman dutifully went off to communicate this. Returning a short time later, he informed the hapless guest “ Mrs. Twombly says she as never heard of Labor Day. The weekend is over today, sir.” I can’t help but believe from stories like these that Florence Twombly served as one of the inspirations for the Dowager Countess Grantham’s character on Downton Abbey.

Like her sister Emily, when the noise and crowds at 54th Street and Fifth Avenue grew too much during the 1920’s, Florence moved uptown into a new house. This home however, was not smaller than her former. Florence commissioned Warren and Wetmore to design a 70-room mansion for her at Fifth Avenue and 71st street.

The house, while not considered one of Warren and Wetmore’s finest works, has a monumentality and severity that perfectly reflected its occupant. The mass and simplicity of its wide 71st street façade also acted as a nice foil to the low horizontal dignity of the Frick Mansion, which it faced. Florence lived there until 1952, when she passed away at the age of 98, maintaining her legendary lifestyle and frosty reputation up to the end. Her mansion was razed a few years later, replaced by a modern apartment building.

The youngest sister Lila Vanderbiltdid not have the good fortune to marry a man with a successful business like her sister Emily, or a shrewd financier like her sister Florence. She chose William Seward Webb. From an old, distinguished New England family, Webb had a propensity for poor business decisions (and a weakness for morphine in his later years). He lavished huge sums on Shelburne Farms, the couple's legendary agricultural estate located on the shores of Lake Champlain. Dr Webb spent prodigious amounts of money trying to develop a new breed of horse; strong enough for farm work, but attractive enough to pull a carriage. The concept might have succeeded had not the automobile and tractor come along while in the midst of his experiment. Owning a Great Camp in the Adirondacks, Dr Webb financed a new railroad (with his wife’s money) in part so he and other millionaire camp owners could reach their private preserves faster and easier. Not content with owning a private railway car (the lear jet of their day) the Webb’s had their own entire private train at their disposal. When Webb died Emily, like her sister Margaret, found all that was left of her fortune was the income from her 5 million dollar trust. Even prior to that it was obvious finances had become tighter. Shortly after World War One she sold her townhouse at 680 Fifth Avenue to John D Rockefeller. Unlike her sisters, Lila never owned another residence in New York City from that point, living in rented Park Avenue apartments when in town, preferring to spend the majority or her time at Shelburne or her Palm Beach estate Mirardo until her death in 1936 .

Next: in Part Two: A look at some in-laws