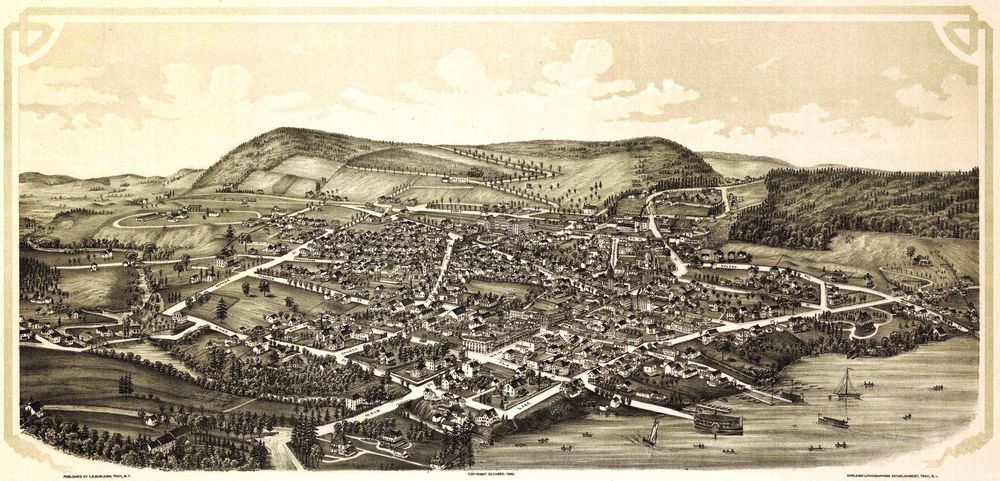

With its compact layout and rich trove of nineteenth and early twentieth century homes, the village of Cooperstown offers a living, three-dimensional, guidebook for fans of historic architecture.

With its compact layout and rich trove of nineteenth and early twentieth century homes, the village of Cooperstown offers a living, three-dimensional, guidebook for fans of historic architecture. I was doubly blessed as a young child to have both a yen for old homes and two great grandmothers living there. On my frequent visits there, I was nearly (but not quite) as eager to see my favorite houses as my elderly relatives, carefully observing the brick detailing and asymmetrical but balanced composition of the Woodcock House next to my Gamma’s, and wondering how a cluster of clearly “modern” colonials came to face the unified row of Queen Anne stick and shingle homes on Pine Boulevard where my other great grandmother lived. As I grew up and learned the stories of these places, along with the individuals and families connected to them, I came to realize these buildings where more than just pieces of architecture, but vital characters in the story of this village that I was irresistibly drawn to. As the names long associated with most with these homes have changed permanently, and the nature of the village itself has shifted over my lifetime, their role has become even more important. Luckily, rigorous zoning laws, well-documented pasts and a unique pride of place have enabled these buildings to remain remarkably intact and well cared for, despite passing out of their builders’ families or old “Cooperstown stock”. They continue to proudly stand, each uniquely contributing to the intricate tapestry that is the history of Cooperstown.

I was doubly blessed as a young child to have both a yen for old homes and two great grandmothers living there. On my frequent visits there, I was nearly (but not quite) as eager to see my favorite houses as my elderly relatives, carefully observing the brick detailing and asymmetrical but balanced composition of the Woodcock House next to my Gamma’s, and wondering how a cluster of clearly “modern” colonials came to face the unified row of Queen Anne stick and shingle homes on Pine Boulevard where my other great grandmother lived. As I grew up and learned the stories of these places, along with the individuals and families connected to them, I came to realize these buildings where more than just pieces of architecture, but vital characters in the story of this village that I was irresistibly drawn to. As the names long associated with most with these homes have changed permanently, and the nature of the village itself has shifted over my lifetime, their role has become even more important. Luckily, rigorous zoning laws, well-documented pasts and a unique pride of place have enabled these buildings to remain remarkably intact and well cared for, despite passing out of their builders’ families or old “Cooperstown stock”. They continue to proudly stand, each uniquely contributing to the intricate tapestry that is the history of Cooperstown.

The downside to my zealous attachment to them is the difficulty in selecting the several houses to feature in this post. I debated picking one stellar example from each architectural style, fashion a “top-ten” list, or examining all the homes on one particular block. I found the task of playing favorite between the dozens I love for different reasons impossible. In the interest of relative brevity, I chose just three. All are “well-known” houses dating from the village’s first half-century, with long interesting histories of ownership, photographed as part of the Federal Government’s WPA Historic Structures Survey, allows us a peek inside and also how remarkably unchanged their exteriors look seventy years later. We begin at the beginning of Main Street, number 1 to be exact.

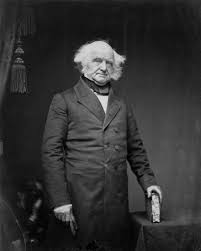

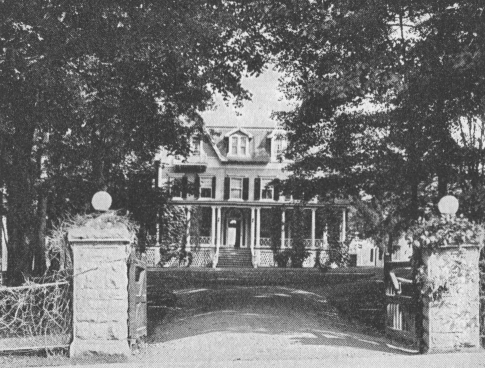

Set on the rise of a hill, Woodside Hall presides over the village’s leafy canopy in all of its Greek revival glory. It was built in 1829 for Judge Eben Morehouse, with terraced gardens embellishing the grounds and a unique Egyptian revival gatehouse that illustrates how well two different revival styles can work together. After financial misfortune forced Judge Morehouse to reluctantly sell his mansion, it is said he could not bear to raise his head in the direction of the ionic-columned temple front when walking on Main Street. Happily for him (and his posture), the reversal of fortune was temporary, and he was soon able to buy back his home. It was during his second period of residency that a US President was lost at Woodside Hall, when Martin Van Buren

After financial misfortune forced Judge Morehouse to reluctantly sell his mansion, it is said he could not bear to raise his head in the direction of the ionic-columned temple front when walking on Main Street. Happily for him (and his posture), the reversal of fortune was temporary, and he was soon able to buy back his home. It was during his second period of residency that a US President was lost at Woodside Hall, when Martin Van Buren failed to find his way through the gardens to the gatehouse in the dark after departing a party there, sheepishly knocking on the front door a half hour later to request a lantern and a guide. It later became the home of Joseph L White. US Congressmen, businessman and adventurer, and one of the key players in William Walker’s ill-fated attempt to conquer Nicaragua,

failed to find his way through the gardens to the gatehouse in the dark after departing a party there, sheepishly knocking on the front door a half hour later to request a lantern and a guide. It later became the home of Joseph L White. US Congressmen, businessman and adventurer, and one of the key players in William Walker’s ill-fated attempt to conquer Nicaragua, Mr. White’s ownership of the house came to an end when he was shot (some say assassinated) on a trip there himself attempting to corner the rubber market. Things quieted down a bit later while Woodside Hall was in the possession of the Stokes family of New York, who made it a center of hospitality and gracious entertaining. About the raciest thing associated with that period might have been when Walter Watson Stokes took as his second wife the pretty Hannah Lee Sherman, great-niece of the famous Civil War General but more popularly known at the time as the Chesterfield Cigarette Girl.

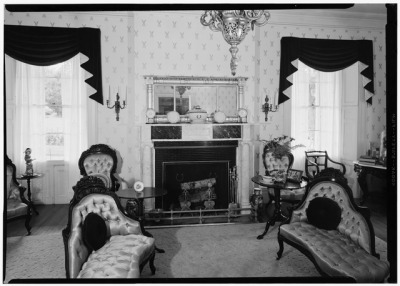

Mr. White’s ownership of the house came to an end when he was shot (some say assassinated) on a trip there himself attempting to corner the rubber market. Things quieted down a bit later while Woodside Hall was in the possession of the Stokes family of New York, who made it a center of hospitality and gracious entertaining. About the raciest thing associated with that period might have been when Walter Watson Stokes took as his second wife the pretty Hannah Lee Sherman, great-niece of the famous Civil War General but more popularly known at the time as the Chesterfield Cigarette Girl. The following photos date from the Stokes tenancy, arguably Woodside Hall's heyday.

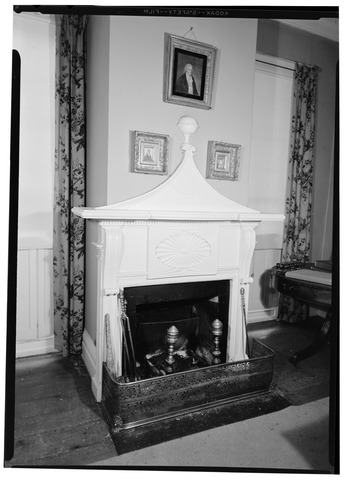

The following photos date from the Stokes tenancy, arguably Woodside Hall's heyday.

While the gardens are long gone, and the residence was converted into an adult retirement home quite some time ago, the property is well maintained and still retains its stately aura. One wonders how many of its current residents know of the colorful pasts of some of their predecessors. Who knows, maybe their stories further add to the roll?

While the gardens are long gone, and the residence was converted into an adult retirement home quite some time ago, the property is well maintained and still retains its stately aura. One wonders how many of its current residents know of the colorful pasts of some of their predecessors. Who knows, maybe their stories further add to the roll?

Walking down Main Street from Woodside Hall, it is impossible to not notice an elegant yellow Federal villa on your right, its beauty enhanced by its sublime setting surrounded by wide lawns and mature trees. Lakelands was built for John Myers Bowers and his charming wife Margaretta Wilson between 1802 and 1805 on a portion of the large land patent the family owned along the east bank of the Susquehanna River. It is said Mrs. Bowers, who had been a great favorite of the Washington’s during her days as young debutante in Philadelphia, immediately elevated the society of the environs upon her arrival. The Bowers began laying out lots in 1791 for a village named Bowerstown on their lands, believing it would soon rise up and eclipse the small town named after William Cooper just a stones through away on the other side of the river. These grand dreams never materialized however. Today only a crossroads hamlet bearing the name Bowerstown and a post-war suburban development called Lakeland Shores hint at the former size of the family’s holdings. After the death of Mrs. Bowers in the 1870’s, Lakelands was sold in 1883 to Schuyler B Steers. Reputed to be one of the wealthiest men in New Orleans, he modernized the mansion, adding a third story under a mansard roof. Mr. Steers and his wife were civic-minded, philanthropic, and popular in the village, generously supporting local charities. Their happiness at Lakelands was not to be long however. In the summer of 1884, their son proposed to a young woman he had long been in love with on the dock at Hyde Hall after a picnic. Upon her refusal, he shot himself in the face, dying instantly. His parents followed him to the grave not long after, with Mrs. Steers dying in 1888 and Mr. Steers in 1889. As a final indignity, his will, which left over $200,000 to establish a home for the aged in Cooperstown under his and his wife’s names was successfully fought in court, the money instead going various nephews and nieces. The Bowers family reacquired Lakelands not long after. Perhaps annoyed by the second empire desecration of the villa’s original federal lines, or maybe to remove scandalous and sad associations with the changes made by the Steers, the mansard roof and third floor were eventually taken off, returning it to its earlier appearance. The following photos were taken soon after that date.

Mr. Steers and his wife were civic-minded, philanthropic, and popular in the village, generously supporting local charities. Their happiness at Lakelands was not to be long however. In the summer of 1884, their son proposed to a young woman he had long been in love with on the dock at Hyde Hall after a picnic. Upon her refusal, he shot himself in the face, dying instantly. His parents followed him to the grave not long after, with Mrs. Steers dying in 1888 and Mr. Steers in 1889. As a final indignity, his will, which left over $200,000 to establish a home for the aged in Cooperstown under his and his wife’s names was successfully fought in court, the money instead going various nephews and nieces. The Bowers family reacquired Lakelands not long after. Perhaps annoyed by the second empire desecration of the villa’s original federal lines, or maybe to remove scandalous and sad associations with the changes made by the Steers, the mansard roof and third floor were eventually taken off, returning it to its earlier appearance. The following photos were taken soon after that date.

Though out of the Bowers family again, probably for good this time, subsequent owners have left appearance of the house unchanged – perhaps they don’t dare, given the sad story of the Steers.

Though out of the Bowers family again, probably for good this time, subsequent owners have left appearance of the house unchanged – perhaps they don’t dare, given the sad story of the Steers.

Walking across the bridge and turning right, one soon encounters Edgewater on the corner of Lake and River Streets. Constructed between 1810 and 1812 for Isaac Cooper (older brother of the novelist), its design was said to be inspired by a house in Philadelphia, with a projecting center bay and shallow pilasters enlivening the mass of this the solid yet graceful house. Passing out of the family after Isaac Coopers death, it became a female seminary for a short time before being bought by the Keese family of New York in 1834. In true Cooperstown fashion, Mrs. Keese was the niece of the late Isaac Cooper, bringing the house back into the family again. They modernized the place during their decades there, most notably with a third floor porch (reputedly for the benefit of their maids) as well as adding elaborate spindles and newel posts to the double curved staircase.

as well as adding elaborate spindles and newel posts to the double curved staircase. Passing out of the family permanently after George Pomeroy Keese’s death in 1910, a new owner had architect Frank Whiting remodel Edgewater around 1920, stripping away the Victorian embellishments, returning it an earlier, refined, if not quite entirely historically accurate look. The following photos date after this remodeling.

Passing out of the family permanently after George Pomeroy Keese’s death in 1910, a new owner had architect Frank Whiting remodel Edgewater around 1920, stripping away the Victorian embellishments, returning it an earlier, refined, if not quite entirely historically accurate look. The following photos date after this remodeling.

The large grounds belonging to the house once continued across the other side of Lake Street, extending down to the shore lake. Later owners retained this parcel after selling the mansion in the 1980’s, building a low modern brick house upon it. Though purists were aghast that a modern home built on the hallowed grounds, the builders were sensitive to their former home. Even without the land across the street, Edgewater still possesses a commanding view of Otsego Lake and the Sleeping Lion from its handsome front steps.

The large grounds belonging to the house once continued across the other side of Lake Street, extending down to the shore lake. Later owners retained this parcel after selling the mansion in the 1980’s, building a low modern brick house upon it. Though purists were aghast that a modern home built on the hallowed grounds, the builders were sensitive to their former home. Even without the land across the street, Edgewater still possesses a commanding view of Otsego Lake and the Sleeping Lion from its handsome front steps.