“How a Guggenheim’s Gatehouse ended up in Red Hook”

What do the clubhouse of the New York Yacht Club, the Department of Motor Vehicles on Warren Street in Hudson, the Columbia County Courthouse, and Grand Central Station all have in common? The architectural firm of Warren and Wetmore designed all of the aforementioned buildings.

Although renowned for their hotels, institutional buildings and of course, Grand Central Terminal, Warren and Wetmore cemented their place in my pantheon of beaux arts architects by creating on of my favorite townhouses on the upper east side of Manhattan, the James Abercrombie Burden mansion. Down the block from the imposing Carnegie and Kahn edifices, the building manages to compete visually with its colossal neighbors (no easy feat) by making a very different statement. Many contemporary urban palaces built for New York’s gilded age elite featured a grand suite of entertaining spaces located on the floor above the ground floor entrance, with private family spaces above and servants’ area beyond that. The exteriors would reflect the interior delineation of space, with second floors tending to have the largest scale, highest windows and architectural embellishment, with each subsequently higher floor gradually diminishing in scale and ornamentation. The Burdens and their architects stood that architectural hierarchy on its head by inserting an entresol for the family’s comfortably scaled living quarters immediately above the ground floor, with the grand public entertaining spaces (with décor inspired by the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles) located on floor above that. With the exterior reflecting the relatively modest second floor, and the third being much grander in proportion, the mansion has a vitality that deviates from the standard grandeur of many similarly scaled urban mansions. The couple that inhabited this unique looking building consisted of a husband whose family fortune was derived from horseshoes and railroad ties, and his wife Adele, a member of New York’s fabled Vanderbilt clan. Combine that with the knowledge that their Long Island estate was used by the Prince of Wales as a base for his 1924 polo playing visit there, looking at the house leaves room for just about every Edwardian, Gilded, and Jazz age fantasy one could imagine.

Burden Mansion, East 91st St

Burden Mansion, East 91st St

As with other well-known New York City architectural firms who worked in the Hudson Valley, Warren and Wetmore’s commissions originated through familial or social connections. The book The Architecture of Warren and Wetmore, by Pennoyer and Walker, explains the Hudson connection from the fact that Whitney Warren as a young man, spent his summers there with his grandmother, a socially prominent Mrs. Phoenix, at her elaborate Italianate countryseat named Glenwood. Having never heard of either Mrs. Phoenix, or Glenwood, I decided to investigate. Thanks to Google, it took very little research to realize that Glenwood is a very well-known local landmark currently being restored, but popularly known as the Plumb Bronson House. I was surprised there is scant mention locally to the connection, or perhaps there is and I just never paid attention. Maybe his grandmother’s tenure there was short, unmemorable or disagreeable. Whatever it might have been, someone evidently liked her, or him, or she had the inside scoop on the architectural bidding or award process in town, as the connection did result in Hudson having two distinct Warren and Wetmore buildings constructed fairly early in the firm’s career.

The first is the former First National Bank building on Warren Street (now housing county offices, including the aforementioned department of motor vehicles). Standing on the corner of Warren and 6th streets, it should be approached from the south, on 6th too be fully appreciated. From that angle, the shallow but well proportioned portico supported by ionic columns, large palladium window and sallow dome rising from the roofline can all be admired. It is an elegant composition, solid with restrained exterior ornamentation. The interiors, although marred by modern institutional intrusions, still reflect the same solid, simple elegant proportions as the exterior.

When it comes to exterior ornamentation, no such restraint was applied to the nearby courthouse they designed about the same time. Swags of ribbon bursting with fruit and flowers compete with heavy Corinthian capitals atop pilasters rising between each window. The pediment is so laden with sculptural elements, one can almost not notice the striking similarity between the eagle crowning its center with those that adorned the exterior of the McKim Meade and White’s late, great Pennsylvania Station. The busy application of ornamentation, while not my favorite, certainly makes a statement, and adds vitality to what might have otherwise been a very plain large building. Sadly, I could not see much of the interior. A trial was in session so the domed courtroom was off limits. The none too friendly sheriff at the door was much more interested in confiscating my camera before allowing me to enter the building than explaining what architectural features could be viewed by the casual visitor, so I opted to try another day.

The third Warren and Wetmore building (that I know of in my environs), holds a special place in my heart because I feel it was my very own discovery, and predates my knowledge of the Hudson commissions of the firm. On a leisurely drive through the back roads of Red Hook one afternoon, I passed a very distinct house. Set slightly back from the road, it’s chateauesque roofline clean white facade and symmetrical proportions lent it a distinctly French feeling, at odds with any other nearby homes, all either earlier farmhouses or post war suburban tract types. The proportions were grand, yet the scale of the house was very livable. I decided if it ever came up on the market, it would be the house I would have to buy (Red Hook property taxes notwithstanding).

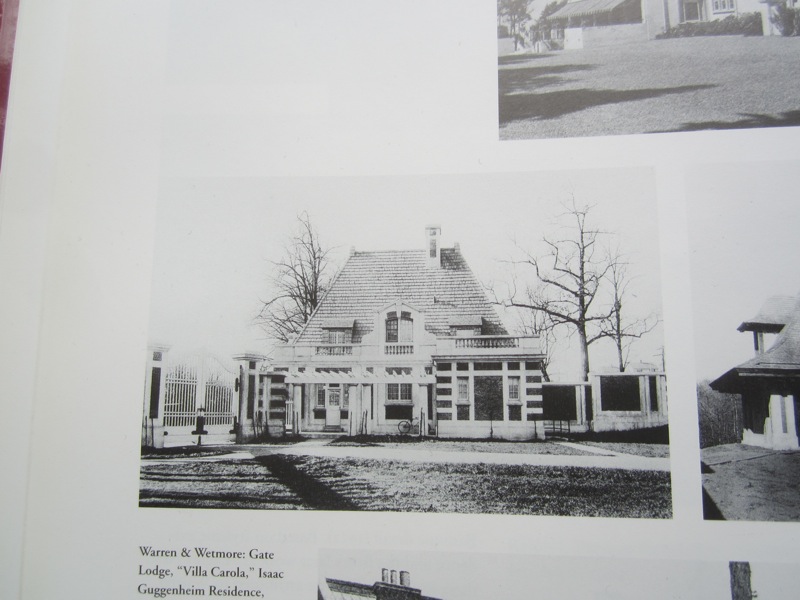

While reading The Astor Orphans, a Pride of Lions, I came across interesting passage. It described one of the characters, Bob Chanler, as having Warren and Wetmore design a house for him on a farm he owned outside of Red Hook. Something in the back of my mind clicked (my mind clicks in odd ways). Yes! I had seen a house very similar to that Red Hook house in an architectural monograph of Long Island Country Houses. I went up to my bedroom and get the book off my nightstand (not your average bedside fare, but I find looking at architecture very calming before going to sleep). Why, the proportions and scale of the white house I admired in Red Hook where a close match to a Warren and Wetmore designed gatehouse on Isaac Guggenheim’s estate in Sands Point! Although the gatehouse was more definitely more elaborate, the similarities were undeniable. Although my affection for the house was bolstered by my hypothesis that it was designed by one of my favorite firms, I wanted some kind of corroboration. Luckily for me, I ran into Wint Aldrich at a party in the area not long after my discovery. Wint, besides being the great nephew of the man who commissioned the Warren and Wetmore house, in an incredible source of knowledge on the architecture and history of the region. Happily, Wint confirmed my theory. The little house that I admired so much, was designed by the same architects as the fabled Burden mansion.

Of course, answers eventually gave way to more questions. The extended Chanler family had employed many leading architectural firms of the day, including Delano and Aldrich and Charles Platt to construct or remodel nearby projects, but I hadn’t heard of a Warren and Wetmore connection. The project would have been a small job for them, and it clearly (at least to me) was an adaptation of one of their earlier designs. In addition, there was no mention of the project or Bob Chanler’s name listed in, the firm’s catalog raissoné. However, as I read more of Pennoyer and Walker’s book, I noticed several mentions of the Chanler name. Not only did Bob Chanler, an artist, execute the murals decorating the Warren and Wetmore designed tennis house on Florham, the Twombly estate, his sister in-law Beatrice Ashley Chanler created some decorative sculptural elements for the Vanderbilt hotel built by the firm in 1913. There was definitely at the very least a business, and most likely social connection between them. Whether Bob admired the Guggenheim gatehouse, and asked them to give him a simpler, scaled down version, or being a modest commission, they just called on one of their draftsmen to pull the Guggenheim plans out of a drawer and do them over for Bob, I don’t know. The truth is probably far from what I imagine, and bears a further in depth conversation with Wint, but that’s for another time. For know I will just hope that maybe someday that house will come up on the market (and that I can afford it when it does). It would be nice to be at Grand Central Terminal with someone, and be able to say “yes, it’s nice, the same architects designed my house too”.