The dog and I both needed a walk early Sunday morning. Hopping in the car, we drove to Wilber Park, parking at the far end of the lower level. Georgia hopped out excitedly, as eager as I was to start our jaunt. While I enjoy going to all of the parks in town on visits home, Wilber holds the strongest associations with my younger years. Adjacent to the Junior/Senior High, it provided a convenient escape route for skipping class. Darting out a side door, then through the parking lot allowed one to quickly slip into the park’s sheltering woods, a temporary respite from the unpleasantness of trigonometry quizzes or Presidential Physical Fitness Exams. Other attachments formed far earlier than my teenage truancy however. Years before, it was where my mother would drop my younger brother and me off on her way to work during the summer for swimming and tennis classes.

reminded me how I would have gladly stood against one of its rough stone walls, a cub scout neckerchief knotted over my eyes, bubblegum cigar clenched in mouth, facing a Mexican firing squad rather than endure my daily swimming lessons.

reminded me how I would have gladly stood against one of its rough stone walls, a cub scout neckerchief knotted over my eyes, bubblegum cigar clenched in mouth, facing a Mexican firing squad rather than endure my daily swimming lessons.

However warm it promised to be later that day, the air temperatures rarely hovered above of the sixties at the ungodly morning hour when they began. Clusters of kids, grouped by age and ability stood in icy water up to their armpits along the pools edge (too young to dive) waiting their turn to demonstrate mastery of one of the basic strokes across the width of the pool and back. Though I would try to blend inconspicuously in the center of my cluster hoping the instructor would not notice me and pass over my turn, vigorous jogging in place or hopping up and down on alternate legs in an effort to keep the blood flowing inevitably had the opposite effect. With a larger than normal head, spindly everything else and no discernable body fat, my natural buoyancy was nil. My twig-like arms and legs propelling the rest of my body through water made as much sense as rowing a longboat with toothpicks. I dutifully went through the motions when my turn came however. Flailing my arms like a windmill and legs scissoring madly, I would churn up as much water as possible to camouflage the fact my feet occasionally touched the bottom of the pool. Coughing, snorting out copious amounts of chlorine-laced water that burned my nostrils as it came out and quivering violently when done, the instructor would occasionally take pity on me (or himself, for I am sure it was quite a painful scene to watch) and overlook one of my other turns (usually the backstroke, which added the dull thud of my head hitting the pools opposite edge in addition to other indignities outlined before).

After what seemed like an interminable audition for the role of a Titanic victim floating in the North Atlantic I would finally be released from my frigid purgatory. Clothes hastily thrown on, a healthy glow would begin to replace frozen pallor as I made my way towards the tennis courts for the next round of lessons.

I would finally be released from my frigid purgatory. Clothes hastily thrown on, a healthy glow would begin to replace frozen pallor as I made my way towards the tennis courts for the next round of lessons.

As soon as tennis ended, attention would immediately turn to the little red and white striped building next to the courts.

or fireballs which appealed to generations of budding masochists.

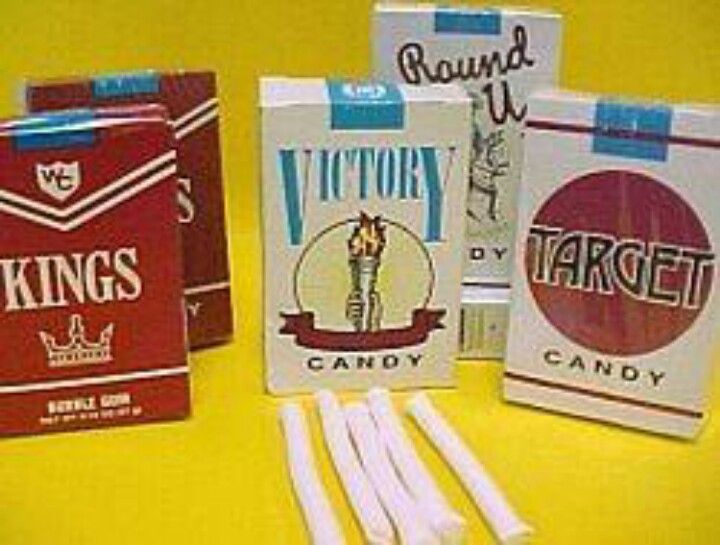

or fireballs which appealed to generations of budding masochists. Candy cigarettes were for days when I was feeling a bit on edge.

Candy cigarettes were for days when I was feeling a bit on edge. This was the first place I ever bought a Marathon Bar, its twelve-inch length boastfully marked off on its wrapper, and learning size isn’t everything in turn.

This was the first place I ever bought a Marathon Bar, its twelve-inch length boastfully marked off on its wrapper, and learning size isn’t everything in turn. Pixie sticks were my candy of choice, their paper tubes holding an alchemic grainy sunbstance that tasted like a mixture of kool-aid and sugar, hold the water.

Pixie sticks were my candy of choice, their paper tubes holding an alchemic grainy sunbstance that tasted like a mixture of kool-aid and sugar, hold the water.

While other kids might head home or back to the pool (for fun of all things) after the lessons, I would my spend my last half hour of the morning exploring the wilder areas of the park, jacked to the hilt on sugar. I may not have been inspired by the athletic feats of Jimmy Connors or Mark Spitz, but I definitely felt a connection with Johns Muir and Burroughs.

Ripped from the plot of an Irwin Allen “Nature Trumps Man” disaster film, developers foolishly clear cut wide swaths of the heavily wooded slopes above the park for a new modern apartment complex. Subsequent torrential spring rains sent several feet of mud hurtling down the hill, oozing across the basketball courts and playground with enough force and velocity to wipe out a whole Barbie village. I remember my mother driving us there to gawk at the destruction, marveling at the closest thing Oneonta would ever come to having to a California-style natural disaster.

Summer mornings in the park would end with my grandmother’s picking us up at lunchtime. Though I dreaded the icy pool each morning and resented missing precious episodes of The Price is Right  or Let’s Make a Deal

or Let’s Make a Deal  (sensing even a young age that the ability to guess the value of a washer dryer or right curtain might prove more valuable later in life than knowing the Australian crawl), when the time came to leave, it was not without reluctance. The combination of candy, pine groves, and creeks can have a surprisingly transformative affect on a child. I might even have been tempted to beg to stay longer, if All My Children didn’t begin at 1pm

(sensing even a young age that the ability to guess the value of a washer dryer or right curtain might prove more valuable later in life than knowing the Australian crawl), when the time came to leave, it was not without reluctance. The combination of candy, pine groves, and creeks can have a surprisingly transformative affect on a child. I might even have been tempted to beg to stay longer, if All My Children didn’t begin at 1pm  (the lure of Pine Valley winning over the Pine Grove every time).

(the lure of Pine Valley winning over the Pine Grove every time).